My mindful interactions with water probably began when I was about 10 years old when I looked forward to summer vacations. Our quarterly trips from Coimbatore to Palghat or Chennai gave me and my brother plenty of opportunities to meander around natural spaces.

The well in my mother’s uncle’s property in Palghat was our favorite. I used to think it was bottomless because the water level never seemed to go down despite heavy use. The well water was used for everything – drinking, laundry, watering the plants, and even bathing their resident dog.

On some hot afternoons, my brother and I would go to the well and peer down, shouting something into the deep abyss. We could hear our voices reverberate back. We were told not to throw anything into the well. As kids, we tend to do exactly the opposite. We would drop light stones, coconut husks and sticks. My eyes used to follow their descent as the item bypassed fringe vegetation and the odd millipedes to hit the water. Life was good.

At my grandparents’ house in Chennai, things were not so idyllic. All of us were strictly instructed to only have ‘bucket baths’ because the tanker lorry would only come after alternate days. Chennai’s tap water carries an unforgettable stench, so baths were not recommended. The house had a well too, but it was mostly shut with a rusty wired pane.

Granny kept an eye on how every drop was used. She would reuse water that remained after every chore – leftover water from cooking rice was used to starch her sarees, small buckets were kept under leaky taps and water from hand-washed laundry was poured on the terrace to cool the house. The water on the terrace would disappear in less than five minutes under the searing Chennai sun.

Back home in Coimbatore, I used to overhear adults talking about how sweet the water tasted and how soft it was on the hair – especially from our relatives who would visit from Chennai. It seemed like there was plenty of water because the city got sufficient rain. No one told us to have bucket baths then.

Three cities, all in South India, had very different relationships with their water. I used to wonder why.

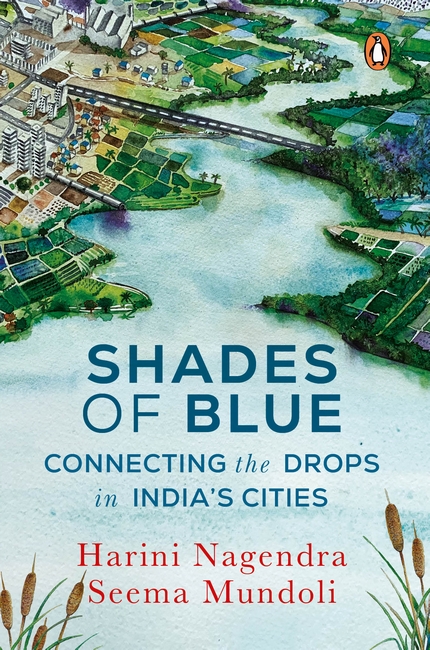

I found the answer 25 years later in Shades of Blue – Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities by Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli. It throws light on the state of our natural water resources and how our relationship with them has changed over the years. Shades of Blue gave me an understanding of how we gradually got to the point where the word ‘stress’ is being affixed to water as if it belonged there. As a fan of water, this newfound knowledge fills me with despair. The verdict is that anthropogenic interventions have resulted in deteriorating water quality, community displacement, and altered ecology – all a harsh reminder of the difficult times we are living in.

Toxic to Tasty

Harini and Seema’s findings, through meticulous research, historical notes, first-hand interviews, and visual notes, drive home the point – our waters are currently toxic. Is there anything that we can do about it?

The answer is maybe. It turns out a few of India’s citizens have taken it upon themselves to conserve whatever is left of our water bodies through public initiatives. Beach cleanups, mangrove restoration projects, campaigns against environmental degradation, and even awareness campaigns about marine biodiversity, offer a glimmer of hope.

Interestingly, marshy wetlands in Mumbai and Kolkata were termed ‘wastelands’ by the British so that they could convert natural infrastructure to suit their economic agenda. Understanding the history of water in India is important for correcting false narratives of the past. This book covers a lot of ground and is deeply moving. It covers the Yamuna in Delhi, the Cauvery in Karnataka, the Pichola Lake in Udaipur to the Brahmaputra in Assam.

It is difficult to find any fault with Shades of Blue. It is transparent, persuasive, and well-researched. One would expect the book to be a tough read coming from two professors. To my surprise, the language is accessible. It is not meant for speed reading since one needs to stop and ponder, and even wonder how, and if, we can bring back the reverence that water demands from us. Without a doubt, Harini and Seema are important and powerful voices in India’s water conservation journey.

After reading Chapter 10 (of the 24 chapters), I take a sip of water and peer into my cup, taking a minute to appreciate the journey it has taken to reach me. However, I’m inundated with a flurry of questions – What did it endure? What microbes is it hosting? Who was put in misery for it to reach my water filter? Above all, how soon can we make things better?

A line from page 245 lingers in the mind – ‘And there is always hope.’

Harini and Seema, faculty at the Azim Premji University in Bengaluru, have been prolific. Their other joint projects include So Many Leaves (2022) and Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities (2019).

Just as climate action is an urgent need, action on water is even more urgent, because, without quality water, nothing else will move. The authors suggest a few bold and practical ways how we can revive and replenish our water bodies.

Harini’s first book in the environment genre was Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future (2016). With a couple of her recent fiction titles doing well, hope she doesn’t get too distracted from writing on nature.