SustainabilityNext reached out to Ravi Chellam, eminent wildlife biologist and conservation scientist, for his comment and possible solutions. He says India has the blueprint to turn things around effectively. A detailed project report for launching a National Mission on Biodiversity and Human Well-being has been prepared. If implemented, it could be a game changer. Edited excerpts:

What’s your immediate response to the Global Nature Conservation ranking?

As a keen observer of the conservation scenario in India, I am not surprised that India has been ranked 176th among the 180 countries assessed while developing the Global Nature Conservation Index 2024. We could quibble about the exact rank, but I am more concerned about what this low ranking reflects regarding the prevailing on-the-ground situation in India.

We can no longer shy away from confronting and challenging the policies and actions, or equally, the lack of policies and inaction, causing environmental and ecological disasters. A shortlist of the things that have hit the headlines include severe air pollution, pollution of freshwater wetlands as well as coastal marine waters, extensive bleaching of coral reef, widespread flooding, catastrophic landslides, scarcity of good quality drinking water, deteriorating quality of soil, frequent severe weather events, rapidly increasing spread of invasive species, recurrent and severe forest fires and frequent incidents of negative human-wildlife interactions.

We shouldn’t forget that there is a huge human cost associated with ecological and environmental problems, and often, it is the poorer and weaker sections of our society who are disproportionately having to bear these costs.

Almost all these problems are a result of human actions, which are destroying functional ecosystems, disrupting global geo-chemical cycles and contributing to unprecedented climate change. While many of these issues result from human actions from across the world, India should never forget that it is among the largest and megadiverse countries in the world with the highest and most dense human population.

The lifestyle of the average Indian has one of the lowest ecological footprints. This provides us with numerous opportunities and places a unique responsibility on us as a nation to provide global leadership. India is very well-placed to provide this leadership as numerous communities co-exist with wildlife, and Nature in all its manifestations is widely revered across the country.

The tragedy is that official policy seems to be hell-bent on a development model which is based on the destruction of Nature and functional ecosystems, a model which typically excludes the local communities. The time has come to call the bluff on such ‘development models.’ Destruction of functional ecosystems and Nature should NOT be dignified by being referred to as ‘development’.

What Measure Can India Take Urgently?

Ecological Restoration

Ecological restoration must become a development priority. Restoration can no longer be an afterthought or an attempt to mitigate the destruction caused by ‘development’ projects. Ecological Restoration must become a mainstream activity, which is recognised as a legitimate tool for development and clear budgetary provisions should be made for these efforts. Such efforts will build our resilience to climate change, connect fragmented habitats, provide habitats for our wildlife, restore the functioning of ecosystems and strengthen the foundations of conservation.

India is Planting Millions of Trees

Our typical efforts at greening including tree plantations are NOT ecological restoration and often end up causing more damage than good. Knowledge-based approaches which include traditional knowledge as well as modern science and inclusive, transparent and accountable models of ecological restoration should be adopted. These efforts should be open for regular and independent monitoring.

Tackling Invasive Species

Invasive species are widely present in almost all habitats across the country. These species are disrupting the natural ecological processes at an unprecedented scale. The widespread prevalence of invasive species degrades the quality of habitats resulting in numerous negative impacts to the native biodiversity and to the local communities.

Knowledge-based and sustained efforts need to be initiated to start controlling and even eradicating invasive species, at least from priority landscapes, including aquatic habitats. Control and eradication of invasive species should be done in strong collaboration with ecological restoration efforts.

Ensuring Connectivity for Wildlife

Our wildlife conservation strategies and actions are largely restricted within the boundaries of Protected Areas, which are, on average, pretty small. Historically, animals have been moving across landscapes even before Protected Areas were established, as well as across human-dominated landscapes, ensuring connectivity between populations separated by large distances.

More recently, wildlife managers have been erecting barriers to restrict the movement of elephants from Protected Areas into human-dominated landscapes. Development of infrastructure like highways, canals, overhead transmission lines, dams, windmills, and large solar parks have all become barriers to such animal movements and have broken the connectivity, thereby fragmenting and isolating the populations of various species into smaller populations.

Construction of all infrastructure must consider the movement ecology of the resident species and provide ways for the animals to continue moving across the landscape, both for terrestrial as well as aquatic species. Infrastructure must not become a barrier. The plans for ensuring the continued movement of animals should be part of the detailed project report of all infrastructure development projects from the very beginning. Wildlife managers must work with local communities and co-create innovative and site-specific solutions and not resort to the construction of barriers for dealing with negative human-wildlife interactions.

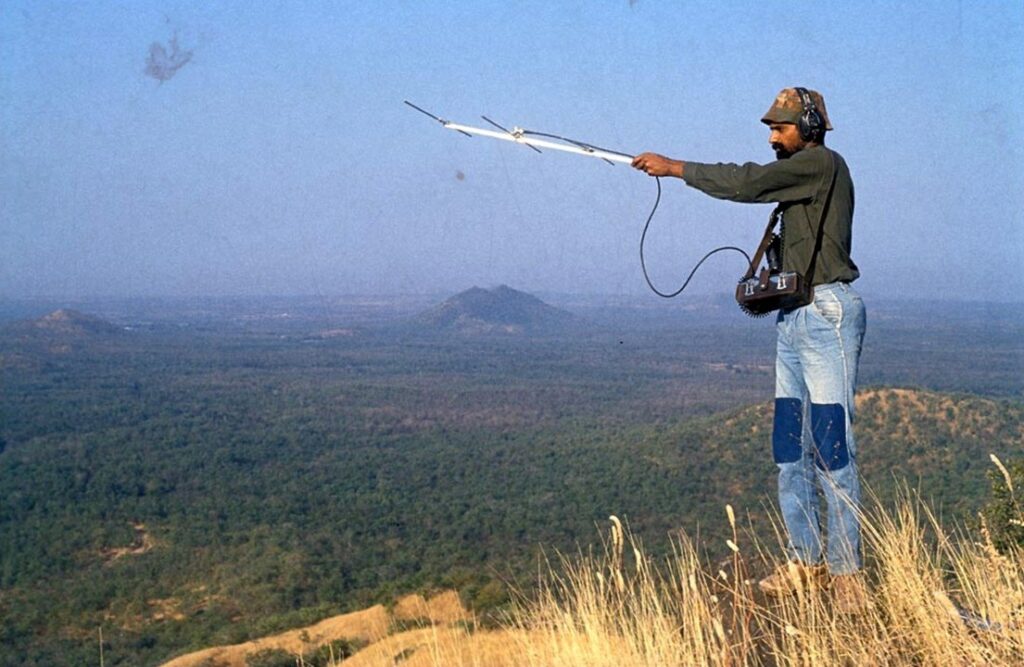

Independent Monitoring

As an urgent priority, researchers and managers must start working as partners. Research should be encouraged and facilitated. Currently, almost all monitoring of wildlife management efforts and wildlife populations is conducted by government agencies. It is crucial to involve competent non-government and academic institutions in the independent monitoring of Protected Areas and populations of endangered species.

Across India, local communities hold copious knowledge related to their environment and biodiversity. Currently, this knowledge is poorly documented and seldom valued or used in management. This knowledge needs to be ethically documented and used to inform research projects, management plans and conservation strategies.

Rule of law

When it comes to matters related to biodiversity, natural ecosystems, wildlife or Nature in general, there is an increasing trend in all sections of Indian society to NOT respect or follow the law. Exemptions are always sought, and exceptions are often made by government policies and orders and by the courts. This results in increasing, long-term and invariably permanent damage to our biological wealth and heritage, which is not easily undone.

On priority, Indian society must recognize that ecological security is fundamental to achieving national security. Instead of diluting our environmental and conservation laws, we should be strengthening them. There should be zero tolerance for those who break the law.

What is the way out?

In many respects, India already has the blueprint to turn things around effectively. Facilitated by the Office of the Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India, a detailed project report for launching a National Mission on Biodiversity and Human Well-being has been prepared. This national mission, when implemented, would be a game changer that will enable India to set the international agenda for biodiversity conservation and provide global leadership.

Ravi Chellam, Coordinator, Biodiversity Collaborative, CEO, Metastring Foundation. Ravi Chellam is a wildlife biologist and conservation scientist who has been involved with research, education, conservation, outreach, and public engagement related to Indian wildlife and biodiversity since the early 1980s. In his career, he has worked with several institutions including the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), United Nations, Development Programme (UNDP), Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) – India, Program, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, Foundation for Ecological Security and Greenpeace India, in leadership positions.