Dr. Ramachandra Guha delivered a fiery talk at a conclave organized by SustainabilityNext and IIM Bangalore’s Centre for Corporate Governance & Citizenship on June 11, 2016. He took the audience through India’s environmental journey from 1915 to the present. While he rued the sad state of India’s environment inflicted by economic liberalization. He is confident that science, civil society and constructive work would lead the next wave. Edited excerpts of the talk:

By Benedict Paramanand

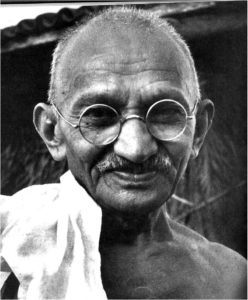

The first wave of environmentalism started when Gandhi came back to India from South Africa – between 1915 to 1950. J C Kumarappa was a Gandhian and India’s first environmental thinker. His book – ‘How to Cultivate an Economy of Permanence’ was path-breaking. He was a pioneer of rural economic development theories. Another Gandhian, Mira Ben, wrote against the indifference of the ‘educated class’ to environment and livelihoods of hill regions. She was also against the idea of large dams. Her thoughts and warnings in her article in Hindustan Times, in 1949, are still relevant but found no favor with the government.

The first wave of environmentalism has significant and relevant lessons for how India makes its policy and treats its ecological resources. But in 1950, it’s voice was not heard since Pandit Nehru believed in big dams and industries to built a new India.

The second environmental wave was between – 1950 and 1991 – when India started its process of economic liberalization. This wave was dominated by mobilization of communities to protest against rampant destruction of forests. The Chipko Movement represented this mood. The major fact to note here is that they were all peaceful yet effective mass protests. These social movements had major impact on public policy with the Government of India setting up the department of environment.

M S Swaminathan’s Green Revolution of the 70s was meant to be a temporary initiative but it stayed on and has led to severe long-term problems. He realized this and advocated the concept of eco-villages. Liberalization led to an anti environment lobby and activists were branded as foreign agents holding back India’s development. The economic reforms have had negative impact on environment. While all other sectors needed to be liberalized, environment needed stricter control with clear policies and governance.

Clearly there are two sides to liberalizations – the bad has led to India turning into an environment basket case where most rivers, including holy rivers, are polluted and Indian cities are one of the most polluted in the world. Unfortunately, the media abdicated its role as a watch dog during economic reforms. In the third wave (1991 onwards) hostility to environmentalists is becoming less severe and the governments are more serious about ecological impact of their policies. Finally, only science, social activism and constructive work, have the potential of taking India forward with manageable impact on the environment.

Watch Dr. Guha’s talk – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mCRnGVlB6Jk

Dr. Guha’s books on Environment

Environmentalism: A Global History (Allen Lane October 2014)

Ramachandra Guha in this book draws on many years of research in three continents. He details the major trends, ideas, campaigns and thinkers within the environmental movement worldwide. Among the thinkers he profiles are John Muir, Mahatma Gandhi, Rachel Carson, and Octavia Hill; among the movements, the Chipko Andolan and the German Greens.

The Unquiet Woods – Ecological Change & Peasant Resistance in the Himalaya

(University of California Press, Revised edition February 2000)

The Unquiet Woods, Ramachandra Guha’s path-breaking study of peasant movements against commercial forestry, it brings the story of Himalayan social protest up-to-date, reflecting the Chipko movement’s continuing influence in the wider world. A new appendix charts the progress of environmental history in India.

Savaging the Civilized – Verrier Elwin, His Trials & India

(University of Chicago Press, August 1999)

Verrier Elwin (1902-1964) was an influential non-official Englishman who lived and worked in 20th-century India. Elwin’s ethnographic studies and popular works on India’s tribal customs, art, myth and folklore continue to generate controversy. Described by his contemporaries as a cross between Albert Schweitzer and Paul Gauguin, Elwin was a man of contradictions, at times taking on the role of evangelist, social worker, political activst, poet, government worker, and more.

Social Ecology (Sociology and Social Anthropology), OUP India, January 1998

A collection of pioneering essays. With the growing awareness of the causes and consequences of environmental degradation, the field of social ecology has assumed enormous importance. This reader provides a ‘state of the art’ survey of the field.

Gandhi was an Instinctive Environmentalist

Gandhi said: “God forbid that India should ever take to industrialization after the manner of the West. The economic imperialism of a single tiny island kingdom – namely England – is today, namely 1928, is keeping the world in chains. If an entire nation of 300 million (India) took to economic industrialization it will strip the world bare like locust.”

If we include China – our population of 2.5 billion – could indeed strip the world bare

like locusts.

Gandhi realized that India needed economic growth and believed in lifting people out of poverty through education, gainful employment, and basic health just like other national leaders. But he was not for industrialization in the manner of the west using energy intensive technologies. Gandhi was an instinctive and an intuitive environmental thinker. He was not a systematic environmental thinker.