Highlights

- Deep-sea mining is intertwined with geopolitics, economics, and environmental ethics.

- The focus should be on improving metal recycling and developing alternative materials.

- The slow pace of international regulation is another incentive for nations and companies to push forward

- Countries don’t want to fall behind in the scramble for ocean wealth.

- Any resource extraction benefits all of humanity – not just a handful of corporations and nations.

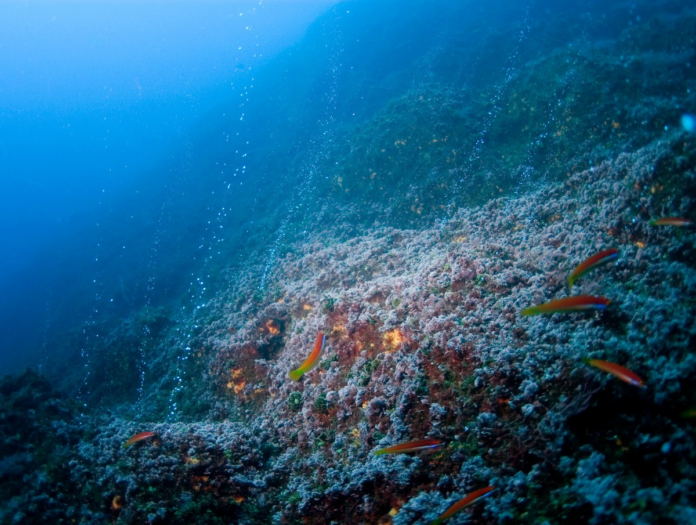

The battle over deep-sea mining is shaping up to be one of the most consequential resource disputes of the 21st century. At stake is not only the extraction of valuable minerals that could fuel the global transition to clean energy, but also the health of one of the planet’s last untouched ecosystems – the abyssal plains of the ocean floor.

The fundamental questions of deep-sea mining are intertwined with geopolitics, economics, and environmental ethics. Who owns the vast, mineral-rich expanses of the seabed beyond national jurisdictions? Should the world pursue deep-sea mining as an answer to its growing demand for critical metals, or are there viable alternatives that can prevent irreversible ecological damage? And are existing international agreements like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) sufficient to regulate this industry, or are we heading toward an unregulated free-for-all?

At the Future Investment Initiative (FII) Institute’s PRIORITY Summit in Miami, Florida, Professor Carlos Duarte, a renowned marine ecologist, and Gerard Barron, CEO of The Metals Company debated the pros and cons of Deep Sea Mining. This important topic and its implications, need to be understood more. So, here’s an article that builds on the FII event deliberations.

The Legacy of Ownership: From Rome to UNCLOS

The world’s current predicament over ocean ownership can be traced back to Roman legal codes. The Justinian Code, which shaped much of Western law, classified the ocean as terra nullius (land belonging to no one) and marine life as res nullius (owned by whoever first captures it). This legal framework laid the foundation for what in economics is known as the “tragedy of the commons,” where open-access resources are depleted due to lack of regulation.

By the 1600s, the Dutch legal scholar Hugo Grotius introduced the “Cannonball Law,” which granted nations sovereignty over coastal waters based on how far a cannon could fire –about three miles. This was later expanded in the 20th century, driven by events such as Iceland’s Cod Wars, to establish Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) reaching 200 miles offshore. Yet, 60% of the ocean remains outside the control of any single country, leaving the deep sea vulnerable to unregulated exploitation.

In 1982, UNCLOS attempted to govern international waters, setting rules for resource extraction in the deep sea. However, the United States refused to ratify the treaty, largely due to concerns about its provisions on metal extraction. This has left the U.S. in a unique position – outside the formal global governance framework but still able to engage in deep-sea mining through alternative legal mechanisms.

The Case for Deep-Sea Mining: Economic Necessity and Geopolitical Reality

Proponents of deep-sea mining argue that extracting polymetallic nodules from the ocean floor is a necessary step to meet the world’s skyrocketing demand for minerals such as nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements. These elements are crucial for electric vehicle batteries, renewable energy infrastructure, and the broader push toward decarbonization.

With land-based mining operations increasingly encroaching on biodiverse rainforests and indigenous lands, supporters of deep-sea mining contend that obtaining metals from the ocean is a lesser evil. For example, 100% of the growth in nickel production over the past four years has come from nickel laterites – deposits found in tropical rainforests. To mine them, vast tracts of rainforest must be cleared, displacing indigenous communities and destroying habitats. Mining companies argue that deep-sea extraction would cause significantly less harm.

Another argument in favour of deep-sea mining is the data-driven approach of modern extraction companies. These firms claim to have collected vast amounts of environmental data – the Metals company has gathered over a petabyte of information – to assess and mitigate potential harm. Additionally, past experiments suggest that some mined areas may recover over time. A commercial collection of nodules in 2022 was followed by a return to the site a year later, revealing encouraging signs of recovery.

Geopolitically, the slow pace of international regulation is another incentive for nations and companies to push forward. UNCLOS was supposed to create a framework for governing seabed resources, but decades later, comprehensive mining rules are still lacking. Some nations, such as China, see this as an opportunity. The Cook Islands, a nation of only 35,000 people but with nearly 2 million square kilometers of ocean space, recently signed an agreement with China to explore deep-sea resource development. Other countries don’t want to fall behind in the scramble for ocean wealth.

The Case Against Deep-Sea Mining: The Risks of the Unknown

Critics of deep-sea mining raise fundamental concerns about the potential destruction of fragile deep-sea ecosystems. Unlike terrestrial environments, which have been extensively studied and can, in some cases, be restored post-mining, the deep ocean remains largely unexplored. More people have set foot on the moon than have visited the abyssal plains, and less than 25% of the seafloor has been mapped.

One of the most pressing questions is whether the damage caused by mining can ever be undone. If these habitats are destroyed, the consequences could be permanent. Scientists simulated “war game” scenarios to determine how deep-sea habitats could be restored after mining – and could not come up with a viable solution.

From a legal standpoint, the lack of a clear ownership structure over deep-sea resources creates risks of geopolitical conflict and exploitation. While international waters technically belong to no one, powerful nations and corporations are moving to claim these resources, often through deals with small, resource-rich island nations that may lack the capacity to enforce ethical mining practices.

The Alternative Path: New Sources and Rethinking Metals

Rather than expanding extraction into the ocean, critics argue that the focus should be on improving metal recycling and developing alternative materials. A major concern is what will happen when 15 million tons of lithium-ion batteries reach the end of their life in 2030 – an environmental crisis waiting to happen, as the technology for recycling lithium safely is still in its early stages.

However, research from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) has demonstrated that lithium can be extracted from brine in oilfields and seawater, offering a potentially massive and low-impact alternative to deep-sea mining. Meanwhile, new battery technologies using graphene or organic compounds could reduce the demand for traditional metals like nickel and lithium.

China has already invested heavily in battery alternatives, and Australian companies are commercializing organic batteries that require no metals at all. If these technologies prove scalable, the argument for deep-sea mining becomes far less compelling.

What about the new High Seas Treaty?

A significant development in ocean governance is the recent adoption of the High Seas Treaty, also known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) agreement. Adopted by the United Nations in June 2023, this treaty aims to address the fragmented and often inadequate governance of the high seas, which constitute approximately two-thirds of the world’s oceans. This agreement represents a landmark effort by the international community to safeguard marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdictions. The current status of the treaty involves ongoing efforts toward ratification and implementation by UN member states.

However, it’s important to note that deep-sea mining activities are exempt from the stricter environmental rules established under this treaty. This exemption has raised concerns among environmental advocates, who fear it could undermine efforts to protect the seabed from potential harm associated with mining operations.

India has signed the High Seas Treaty in September 2024. India is also advancing its deep-sea mining capabilities – in October 2024, the National Institute of Ocean Technology conducted a successful exploratory mining trial in the Andaman Sea to extract polymetallic nodules.

The Way Forward: Regulation, Alternatives, and Responsible Extraction

The path ahead requires balancing economic necessity with environmental responsibility. If deep-sea mining is to proceed, it must be governed by clear, enforceable regulations that ensure minimal harm to marine ecosystems. Mining companies must be required to prove, with independently verified data, that they can restore affected environments. Without such assurances, a moratorium on deep-sea mining may be the most prudent course.

At the same time, alternative sources of critical minerals must be aggressively explored. Governments should fund research into these solutions and incentivize industries to transition away from resource-intensive technologies.

The deep sea represents both a promise and a peril. How we choose to govern and use its resources will shape not only the future of technology but the future of the planet itself.

Finally, the world must confront the legal and geopolitical gaps in ocean governance. The 60% of the ocean that lies beyond national jurisdiction should not be treated as a lawless frontier. Instead, international cooperation is needed to ensure that any resource extraction benefits all of humanity – not just a handful of corporations and nations.

Kashyap Kompella, CFA is an industry analyst, author, and advisor on transformative technologies. He served as the co-chair of IEEE Planet Positive 2030 Economics and Regulation Committee.