Bangalore is a city of lakes that date back to the 15th Century. Hebbal lake being the largest lake of Bengaluru, spanning 150 acres. In the wake of increasing environmental concerns and the precarious state of Bengaluru’s lakes, this article attempts to offer a comprehensive guide for concerned citizens and authorities alike. The piece not only highlights the challenges faced by these water bodies but also provides practical solutions to ensure their survival (Lohr, V. et al 2016).

Every lake has its own history, identity, aura and ecosystem which must never be tampered with. Lakes have the responsibility to recharge groundwater in and around their periphery for about 10-15 feet and allow for water to trickle its way to recharge the aquifers (Scanlon, et al 2019). Lakes have the ability to monitor micro climates. They add beauty to its ambience. Lakes provide good lung spaces to a busy city like Bangalore. They are home to many species too.

Rains fill lakes and lakes swell and join rivers and rivers gush and join the sea, this is a universal norm around the world Gleick, P. H. (2018). FOL, with nearly two decades of experience in lake conservation, recognizes the common dilemma faced by citizens, who express deep concerns about their local lakes of Bengaluru but often find themselves stuck in a loop of complaints. This article aims to bridge the gap between concern and action by presenting a step-by-step guide, akin to a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) with an escalation matrix.

Bangalore has 167 lakes managed by Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) as shown in figure 1. The other authorities such as Bangalore Development Authority (BDA), Karnataka Forest Department, Lake Development Authority & Bangalore Metro (BMRCL) all put together manage 210 lakes of Bengaluru. Lakes that were surveyed were 104 and 85 lakes had fences and lakes that were developed were 65, work in progress were 24 and yet to be developed were 3 and in total were 92 as per BBMP.

Survey conducted by Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) shows that out of the 167 lakes in Urban Bengaluru, when water samples were collected of 41 lakes, nearly 39 lakes were categorised into ‘Class E’ (not suitable for fishery) and not even a single lake falls into A or B category (suitable for drinking) as shown in the figure 2.

Investigation of Few Lakes of Bengaluru:

India’s first Conservation Psychologist, Earthitude Research Forum, Co-Founder Friends of Lakes (FOL), ISO 14,001 Environmental Auditor, Sustainability Reporting, Research Scholar

The efforts of FOL, which is associated with 22 lakes across Bengaluru, has always been able to handhold communities to form lake groups around the lake and be watch dogs to manage their own lakes. Lake groups consisted of birdwatchers, walkers, cultural groups who conduct various eco-friendly activities, environment group, tree watchers and huggers, compost management for green waste derived from the lake and wet waste from various sources, water quality group and other voluntary groups.

In this regard initially, the group engaged in cleaning lakes off garbage it contained and making walkways to set the communities to conserve the lake Ex Chalkere, which was too bushy to venture into and where Kere Hubba was conducted. Soon the groups were empowered to manage it and then started to include visits from many officials to inspect the historical Singapura lake for various problems that ranged from encroachment to politics that aimed to destroy it.

Then again, Doddabommasandra lake was encroached in the name of development and communities were engaged in showing activism to save their lake from it being grabbed to make commercial infrastructures. The shrinking Uttarahalli lake was made to accommodate more sewage water in the name of development (Chen, X. 2020). Jakkur lake was a model lake for Bangalore as it is a community run lake, which took charge of the lake from a more holistic approach. Rachenahalli lake got filled with so many borewells within the lake to water its plants when tertiary treated sewage water use would have been a good option.

Yelemallappa Chetty lake, one of the oldest lakes of Bangalore dying slowly with effluent filling the lake day in and day out. Kalkere Rampura lake got separated by the road that divided them and dumped them with construction debris. Hebbal Lake every year suffers the aftermath of Ganesh Charturthi and POP idol immersions that contaminate the lake and soil.

| Class | Suitability |

| A | Drinking water source without conventional treatment but after disinfection |

| B | Outdoor bathing organised |

| C | Drinking water source with conventional treatment followed by disinfection |

| D | Propagation of wildlife and fisheries |

| E | Irrigation, Industrial cooling controlled waste disposal |

Challenges Faced by the Lakes of Bengaluru:

We spoke to some Engineers from the lake department of Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and asked them what according to them is a developed lake? At best, their response was sketchy, as they were unable to classify a lake as developed or in the process of being developed. Their response to the questions seemed they were very confused about how they would tag a lake that is developed, development in progress or undeveloped. On further probing, in a meek voice, one Engineer said, “a lake can be called developed if there is no sewerage entering into it”. This again gives rise to a fundamental question whether BBMP understands what is the real meaning of a developed lake?

A lake has its own ecosystem with its own thick foliage of green cover all around in which birds, insects, reptiles and aquatic animals thrive on this sanctum sanctorum filled with pristine rainwater. But with man wanting to be the only dominant species on Earth, he leaves the others no choice. People have lost that connection with public assets and don’t consider it their property to conserve it. Concrete jungles are more prevalent in these open spaces. Maintenance of lakes, water bodies is one of the biggest challenges that our country is facing. The Government expects private corporations to use their CSR funds to maintain/adopt lakes.

Water is a state subject, therefore most provisions and regulations are laid down by the local governments. So for a bit let’s focus on one of the biggest problems of lakes: Encroachments; encroachments can be done in various ways, either by means of one converting the lake land to their name over a period of time or by changing the identity of the piece of land, also they become encroachers. Lakes are used for commercial purposes and converted slowly into parks & playgrounds, have unnecessary structures and incorporated convention/function halls, theme parks etc, into the lake and such structures don’t contribute to the conservation of lakes, but do the inverse, for example, In the name of desilting Doddabommasandra Kere in North Bengaluru, the lake was dumped with soil to the maximum extent to make a parking lot, huge parks, open gymnasiums, large gazebos and pave way for other commercial activities by using lake and forest lands.

The construction of a temple, government office, themed water park, restaurant, sports complexes and court for different hand games like badminton, throwball, shopping complexes etc are also encroachments, just that this time, the government is also the contributor to the identity loss of the lake. The government officials also say that the lakes will get filled with water by their efforts, but that is not the case in many lakes, as the lakes don’t get filled with good rain water until desilting of stormwater drains happen, when garbage and construction debris is cleared off the storm water inlets, so that only pure rain water enters the lakes. Eco friendly festivals were propagated by FOL. POP Ganesha immersion was very prevalent which was heavily objected to and ensured an alternative to POP was encouraged by KSPCB and BBMP so that lakes can be free from POP and the heavily painted led Ganeshas.

Many miscreants somehow manage to throw their sanitary water into the lakes directly and the government doesn’t penalise anyone, even after NGT slaps BBMP with hefty fines of 500 cr and more just from one lake. Mind you, the penalty paid by BBMP is all the hard earned tax money of the public and we don’t even know in what ways the NGT puts these collected fines to proper use. Also lakes like Belandur, Yamaluru and Varthur are victims to detergent and cleaning agents from residences and industries that make it to froth and burn for weeks together. So as per NGT they claim that these collected fines are diverted back to BBMP for conducting the required lake conservation activities but ground reality shows a different picture even after BBMP gets penalised. Fish kill is noticed very predominantly in Sankey tank, as they have a swimming pool next door. There is no perceptible change in the lake, it only seems that the collected penalty is getting rotated from BBMP pockets via NGT back to BBMP.

On the other hand, another major issue that lakes face is that due to lack of maintenance the STP’s are getting defunct, which means a few crores of tax money of the public are getting wasted. Some STP’s have water but not enough that they have to borrow raw sewerage from other lakes and then treat it for use for gardening purposes, at the same time some apartment STP’s are so full with treated water after use in their own gardens, that some treated water has to be let into the nearby lakes, hence, I sincerely hope that a feasibility study is conducted before designing and building the STP’s, so government can save some tax money of the public Tchobanoglous et al (2019). Either way, Bangalore lakes have not been free from sewerage, irrespective of all the efforts of the government. Rajakaluves (large storm water drains) across the city have been encroached and clearing that will now be an uphill task for BBMP.

Recommendations:

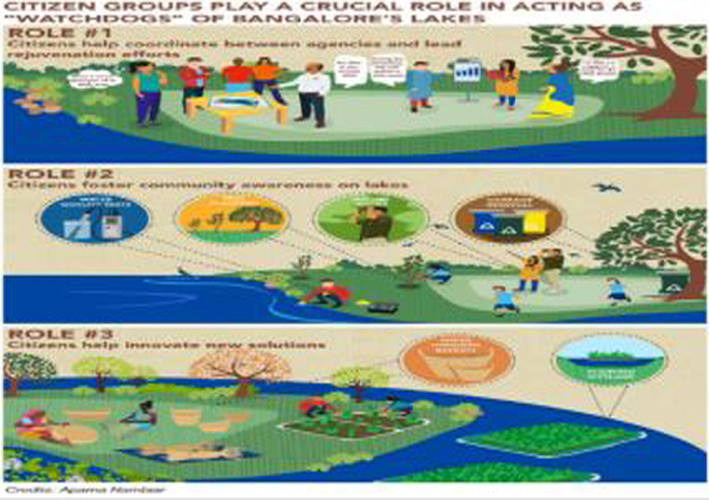

Community Engagement: The Bengaluru city lakes call for greater public engagement and awareness, urging citizens to take ownership of their local lakes. The importance of forming lake groups, conducting surveys, and collaborating with relevant authorities is emphasised. “Kere Hubbas” (lake festivals) are suggested as a means to increase public awareness, footfalls and engagement. It advocates for active public engagement and the formation of lake groups to identify and prioritise developmental works. A lake is the property of the public and the government is the authority to manage it. It is like an amenity that needs to be managed by both the government and its people. Responsibility of the public is to act like the local watchdog of their own lakes as illustrated in figure 6. NGO’s and all other interested parties must come forward to use their CSR funds for the benefit of the society.

Further, the public needs to first form a lake group of all the interested parties and start to identify activities for developmental works. They should prioritise collection of data based on its geographical location, size, landmarks, depth, quality of water, aquifer mapping, ecological identity (flora & fauna), encroachments and other illegal activities in the lake premises, study the upstream and downstream of the lakes, connecting storm water drains, desilting the lakes and rajakaluve networks etc. Most of the activities, the group may need help from surveyors of the revenue department, regional officers of the pollution control board to regularly take lake water samples and generate reports to maintain their lakes. Lake authorities, home guards and police have to be actively involved in preventing illegal activities and protecting the lake. The civil departments of the local municipal council maintain the lake, so keeping in touch with BBMP lake Chief Engineer (CE) and his set of engineers and inspectors always helps.

Government Accountability:

The article also suggests legal avenues for seeking justice for lakes, involving entities like the National Green Tribunal. The involvement of surveyors, pollution control board officers, and collaboration with various government departments is emphasised. Government has to manage lakes or give it to private entities for better maintenance.

The author holds the government accountable, suggesting the need for better management or private entity involvement in lake maintenance. The Karnataka Tanks Conservation and Development Authority (KTCDA) is spotlighted as the highest regulatory authority, albeit deemed ineffective and corrupt. The ministry of minor irrigation and ground water development department also is responsible to manage the developmental works of lakes. Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) is also another government authority to enforce lake protection and conservation. The Local municipal corporations (BBMP) – lakes departments like BBMP- Lakes & forest departments. Bangalore Metropolitan Task Force (BMTF) is the watchdog of BBMP. Local water and sewerage boards like Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). Karnataka state disaster management authority (KSNDMC) with its state office in Attur, Bangalore, also is a stakeholder for lake management.

Also the Central Government Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF) has some guidelines regarding lake conservation. The National and State Water Policy barely quote lakes, let alone its protection and conservation. Implementation of the policy itself is questionable.

This article advises citizens to take legal routes when necessary to protect lakes and involving entities like Lokayukta and reaching out to the Supreme Court, High Court, or the National Green Tribunal (NGT). Key acts and rules related to lake conservation are highlighted for citizens’ awareness and use timely. One can also take the legal way to bring justice to lakes by reaching to the Supreme Court, High Court or the National Green Tribunal by understanding the nature of the problem. It important to know what are some of the key acts & rules that one must be aware of before considering conservation of lakes or lobbying for lakes which are as follows:

- Environment Protection Act 1986

- Water Act 1974

- Wetlands Rules 2017

- KTCDA Act 2014

- Karnataka Land Revenue Act 1964

- Karnataka Irrigation Act 1965

- KMC Act 1976 and resolutions, etc

- Karnataka Groundwater Act 2011 & 2012

The sanctity of the lake has to be maintained for its own ecosystem. Allowing a variety of trees to naturally grow which houses many birds, insects, reptiles etc will balance the ecosystem. Adding a variety of fish, frogs, tortoises and a range of aquatic plants will maintain the lake’s diversity. Reducing the eutrophication of lakes is also a continued process. Tertiary treatment of sewage water is of utmost importance before letting the treated water into the nala or the sale of treated water is also a good starter kit for lake maintenance. As responsible citizens of our country, it is our duty to hand over lakes and other green, clean & safe patches to the next generation as a token of love and care for them as well as nature. Just by maintaining our lakes in Bengaluru, we can get sufficient potable water and it is high time people are water and environment-conscious at large. So, come let’s rejoice and celebrate “Water”.

In conclusion, the article advocates for a holistic approach to lake preservation in Karnataka. It calls for collective responsibility, involving government bodies, the public, and corporate entities. The article underscores the urgency of maintaining the sanctity of lakes, preserving their ecosystems, and promoting sustainable practices (UNSDG 2015). By instilling a sense of ownership and raising awareness, the article envisions a future where lakes in Bengaluru and beyond become sources of clean water, thriving ecosystems, and symbols of responsible environmental stewardship. By emphasising the importance of understanding nature’s laws and avoiding concretization, the article envisions a future where lakes become sustainable sources of clean water, vibrant ecosystems, and cherished legacies for generations to come.

References: (*indicates a primary source)

- Gleick, P. H. (2018). The World’s Water Volume 8: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. Island Press.

- Tchobanoglous, G., Burton, F. L., & Stensel, H. D. (2019). Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery. McGraw-Hill Education.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN General Assembly.

- Chen, X., Liu, G., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Review on urban water reuse: A multi-disciplinary perspective. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 14(5), 84-102.

- Lohr, V. I., Pearson-Mims, C. H., & Boehm, R. (2016). Water reuse for non-potable applications: A review of social, institutional, and economic factors. Environmental Science & Technology, 50(8), 4535-4545.

- Scanlon, B. R., Faunt, C. C., Longuevergne, L., Reedy, R. C., Alley, W. M., McGuire, V. L., & McMahon, P. B. (2019). Groundwater depletion and sustainability of irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(24), 9320-9325.

*https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/bangalore-lake-revival-solutions-part-2-21106

*https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/bbmp-plans-to-build-road-on-lake/article19453464.ece

*https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/wetlandnews/news-2015/decc-lake-revival.pdf

This article is reproduced with the author’s permission.

It was first published in Urban Kaleidoscope: Water and the City, Vol. 2