With the capability to extract rare metals from 20 million mobile phones a month, two college buddies are striving to make India less dependent on China. They are taking their expertise global too. They could do with a better-regulated market and policy support for e-waste management.

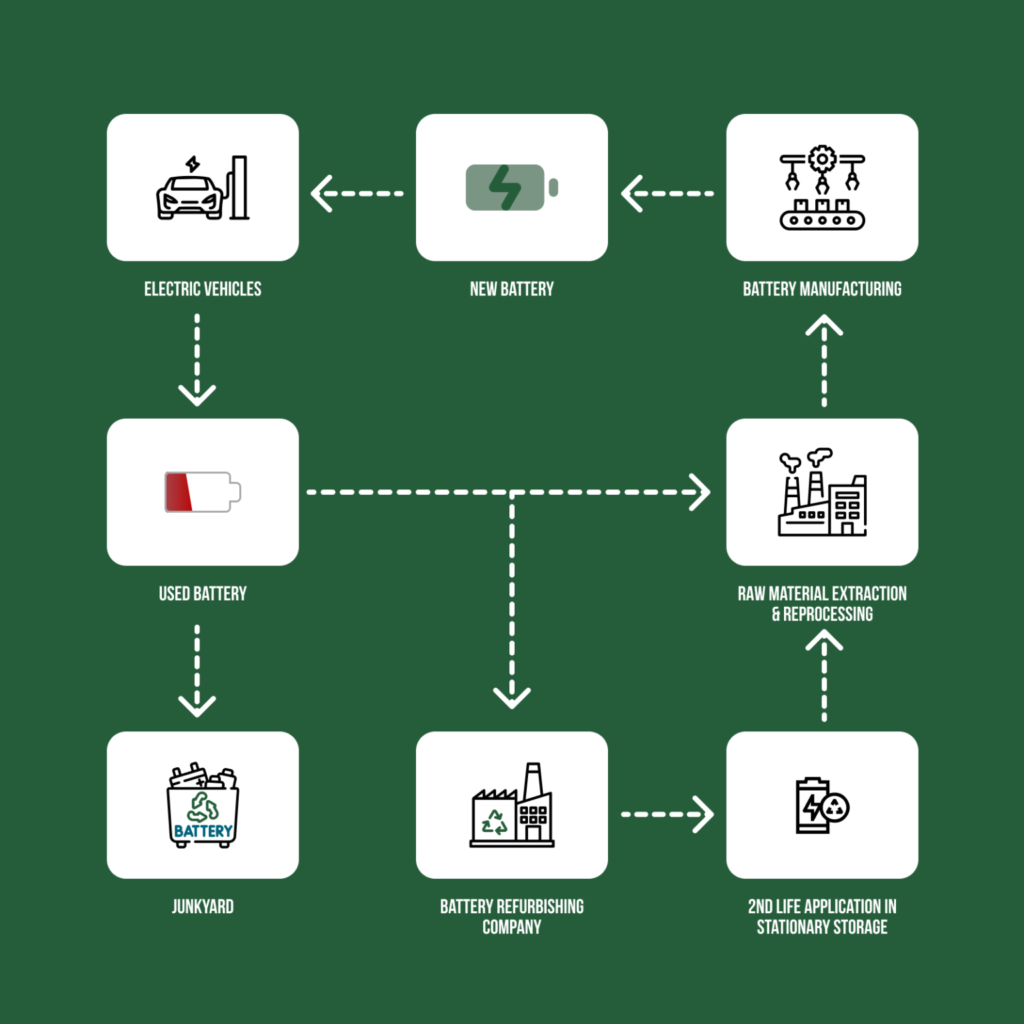

BatX Energies Pvt. Ltd., co-founded by Vikrant Singh and Utkarsh Singh, specializes in the recycling of end-of-life lithium-ion batteries. The company’s focuses on the extraction and reuse of rare earth metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. It aims to contribute to a Circular Economy by ensuring these materials are recycled and reused for producing new batteries, reducing the need for new raw material extraction. It operates from the Sikandrabad Industrial Area, Bulandshahar in Uttar Pradesh.

Vikrant Singh recently shared his entrepreneurial journey in a conversation with Benedict Paramanand, Editor of SustainabilityNext. In this candid conversation, Vikrant elaborates on the challenges and progress of the Indian battery industry in creating a sustainable and organized market for recycling batteries. Edited excerpts:

Vikrant, can you tell us about the inception of BatX Energies?

Our journey began in college at BML Munjal University, where we were passionate about building cars and participated in international competitions. It was in 2016, during my second year when we needed Lithium batteries for an EV car project, but they were neither available in India nor affordable. This challenge sparked the idea of BatX – to address the gap in the Lithium battery market in India.

How did you move from car building to battery recycling?

Initially, our focus was solely on technological solutions. We aimed to build the first lithium-ion cells in India. Utilizing the college’s advanced material research centre, we spent two years developing our skills in nanoengineering and even published a paper on our findings. However, the realization that setting up a battery cell manufacturing unit required significant capital made us opt for recycling. We noticed the scarcity and high cost of integral materials like Cobalt and Lithium, which led us to explore extracting these from old cells.

What is the current focus of BatX Energies?

We started by creating second-life battery packs from scrap batteries, primarily from the telecom and electronics sectors. We reinvested our profits into R&D for recycling. By 2021, we had established our first commercial recycling plant. We specialize in producing ‘Black Mass’, a mixture of nickel, magnets, lithium, and graphite obtained from used batteries. We can recover about 80-85% of Lithium with 95% purity.

Where does your raw material come from, and where does the extracted lithium go?

We source used batteries entirely within India, focusing on portable electronics and OEMs like Tata and Mahindra. The extracted lithium, due to the lack of a local manufacturing ecosystem, is mostly exported. We’re keen on contributing to a sustainable and circular economy, ensuring that EVs remain a greener alternative.

How does BatX Energies fit into the global market, given the current focus on local sourcing?

We’re expanding globally and are in talks about setting up processing plants in Singapore, Texas, and Africa. The strategy is to process batteries locally in these regions to create black mass and then transport them to our facilities for further extraction. This global expansion is part of our strategy to create a circular economy and reduce dependency on new mining.

What is the current status of lithium discovery in India, and what are the challenges associated with its extraction?

As a member of the technical team involved in this area, I can share that we have conducted level testing on the discovered lithium in India. The major challenge we face is that the lithium here is in rock form, whereas 80% of the world’s lithium is found in liquid or brine form, like in Congo, Chile, and Argentina. The concentration of lithium in Indian rocks is very low, around 10 parts per million (PPM). This means that one ton of lithium rock will yield only about 15 to 20 grams of lithium. The economic viability of extracting lithium from such low concentrations is still a significant challenge.

Additionally, with the current market dynamics where lithium prices have dropped, it raises the question of whether mining domestically is feasible compared to importing. The practical stage of starting extraction in India, especially with the recent findings in Rajasthan, is still several years away, possibly five to six years, if it proves to be recoverable at all.

China is the only country that has successfully exported lithium from similar rock forms, and India currently lacks companies with this expertise. The government’s involvement or partnerships in this area are still unclear, but as of now, there remains a question mark over the concentration of lithium in the rocks and the feasibility of its extraction.

With the evolving landscape of battery manufacturing in India, how does BatX Energies plan to contribute?

We are engaging with cell manufacturers for recycling not just end-of-life batteries but also production rejects. Our goal is to create a domestic supply chain for recycled materials, collaborating with manufacturers to bolster cell production and technology indigenization in India. This approach is aimed at fostering a sustainable, self-sufficient ecosystem for battery manufacturing and recycling.

How do the standards and quality of mobile batteries compare with those used in vehicles, such as two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and four-wheelers?

The quality and standards of batteries vary significantly across different segments. For two-wheelers and three-wheelers, the batteries used are generally of lower quality compared to those in four-wheelers. The standards for four-wheeler batteries are much higher and are often determined by government policies. For instance, in the case of four-wheeler batteries, AIS 48 certification is necessary for selling these batteries. While in India, due to the lack of cell manufacturing indigenization, material-wise segregation of batteries is challenging. This segregation is primarily done based on electrical parameters, like the capacity of mobile phone batteries, but the exact amount of lithium in these batteries is often unknown, marking a key difference in battery manufacturing and standards between India and countries like China.

With the emergence of other extraction companies in India, like ReSustainability in Hyderabad, do you view them as competition for BatX Energies?

I don’t see any competition with other companies because the market is vast, and there’s room for many players. We consider these companies more as partners rather than competitors. The focus is not on competing within the Indian market, but rather on how we can collectively reduce dependency on imports, especially from countries like China. The development of more companies in India will help boost the battery recycling and manufacturing sector. Given the size of the Indian market and the second-largest population globally, there’s enough scope for multiple recyclers without significant competition.

What are the key incentives or support that recyclers need in India to grow and become more effective in their operations?

First, the government should focus on organizing the market and giving recyclers the authority to store and handle batteries. This regulation is crucial for creating a regular supply chain. Second, there should be production-linked incentives for recyclers, encouraging them to produce more lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Third, policies should be more stringent for battery producers in terms of recycling their products, ensuring materials are not dumped irresponsibly. Cobalt, for instance, is a heavy metal that can be highly polluting. Lastly, the government should consider providing subsidies in areas like electricity or land to attract investment and support the recycling industry. This approach will not only make the sector more profitable but also contribute significantly to environmental sustainability.

Can you describe the scale of your battery recycling operations and the challenges involved?

We are recycling the equivalent of 20 million mobile phone batteries each month. The major challenge we face is the collection of these batteries, as there hasn’t been a systematic collection process in India for many years. To tackle this, we’ve created an online platform for digitalising collection centres, facilitating the collection of batteries from states like Odisha, where the supply chain and collection bandwidth are limited. These batteries are often discarded or lying uncollected in various places. By establishing state-by-state systems for battery collection, we are not only cleaning up the environment but also creating local job opportunities.

We currently pay around 200 rupees per kilogram for these batteries, which incentivizes collection. Our operations are divided into three segments: R&D, where we keep abreast of changing battery technologies; production, where we extract materials like lithium; and supply chain management, focusing on battery collection and transportation. This work is groundbreaking in India, and our team is highly motivated to drive innovation and expand our capacities in this new and exciting field.

Edited by J Shiruti