If the plan to make Nilgiris a carbon-neutral zone is to become a reality there is a need to define its tourist carrying capacity and adhere to it. Since Nilgiris is gifted with a commitment bureaucracy and vigilant citizenry, chances of this pristine region regaining its glory is high.

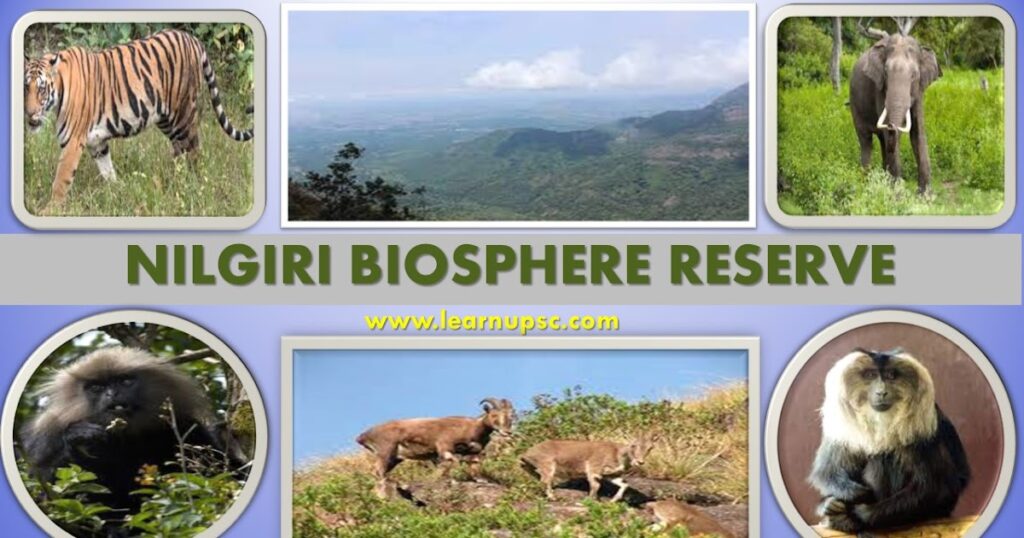

In June 2023, Supriya Sahu, the Additional Chief Secretary, Environment, Climate change and Forests of the Tamil Nadu Government announced a plan to make the mountain district of Nilgiris a carbon-neutral one. With Shola forests, pristine grasslands and clear streams, the Nilgiris District in western Tamil Nadu is home to many endemic species of flora and fauna. With this announcement, the district joins the list of mega-cities and cities around the world that have pledged to become carbon-neutral.

Net-zero emissions or carbon neutrality can be achieved when the amount of carbon-di-oxide emissions is almost equal to the absorption capacity. This can be achieved by increasing forest cover and switching to alternate fuel sources. Though a welcome move for a biological hotspot, do the sustainable needs of an ancient mountain district end there? Here are some aspects that need immediate attention in the district.

The Menace of Tourism

In the summer of 2023, a record number of 8.61 lakh tourists visited the Government Botanical Garden in Ooty. The Tourism Department of TN uses this number as a rough estimate to analyse the visitor flow into the district. This number is most certainly an underestimate considering that many tourists avoid visiting the Botanical Garden due to the crowd. The plan to introduce electric vehicles to reduce emissions is a welcome move. However, the proposal does not address the increasing number of cars and the rampant cutting of native trees on the edges of major roads by the Highways Department for extension.

With the rapid increase in tourist inflow, there is a growing demand for hospitality infrastructure that brings investors from all over India. As per the data presented by Vasudha Foundation during a session on Carbon Neutral Nilgiris by the Department of Environment and Climate Change in June 2023, the district has seen an unprecedented rise of 138% in the built-up area since 2001.

Some resorts and homestays have no consideration for environmental impacts and they operate without the required regulations. In 2018, the district administration under the then collector Innocent Divya shut down 11 resorts functioning without approvals in the buffer zone of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve.

In October 2022, the tourism department initiated a study to analyse the eco-tourism aspects in The Nilgiris. It would be beneficial for the locals if the results of the project were made available to the public and their opinion sought before the measures are implemented. Without addressing tourism and its implications in the district, a sustainable future is a moot discussion.

Shola Forests

Enhancing green cover is the primal way to create a carbon-neutral environment. The Shola forests of the Nilgiris, classified as Tropical Montane Wet Temperate forests by Harry George Champion, a forest officer of British India, is a complex ecosystem of trees, grasslands and epiphytes. W Francis describes the Shola trees in his book The Nilgris, first published in 1908 as slow growing varieties which take at least a century to mature.

In his essay, Observations on Shola Forest, Michel Danino, a scholar of Indian history explains that most trees in the Shola Forest take five years to reach a height of one to two metres. With his experience of living on the edges of the woods in the Nilgiris for over two decades, he adds that a fully grown tree in a healthy Shola is around fifty to hundred years old. Resurrecting a Shola ecosystem is not easy and preservation may be the best weapon against species loss.

Shola grasslands are crucial to the ecosystem and have undergone severe habitat loss for many decades now. Among the threats to the forest-grassland ecosystem, as mentioned by Sasmitha and others in their paper Ecosystem Changes in Shola Forest- Grassland Mosaic of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, are the rapid spread of invasive exotic species, commercial plantations, monoculture, cattle grazing within reserved forest region and climate change. The authors suggest identifying the knowledge gap and extensively mapping the loss of grasslands and the spread of invasive species as remedial measures.

Commercially valuable trees were introduced during colonial times and were continued by the forest department until 1990 to meet industrial needs. Vast areas of grasslands were destroyed for this purpose. Given the easy adaptability and fast growth of these trees like acacia, they tend to spread to the nearby forests, hindering the growth and spread of native species and grasslands.

Senthil Ramakrishnan, a social activist and author of Aboriginal Badugas of Nilgris, says when it comes to conservation policies, wetlands and grasslands are often overlooked. He says construction undertaken in the vicinity of the forest though it may not necessarily fall within the designated reserved region, is a significant threat in The Nilgiris. He points to the rapid spread of exotic species like wattle and cypress in Longwood Shola in Kotagiri, a reserved forest in the heart of the town. He adds that if the spread of these species is not curbed, the survival of native trees is tough.

Citizen Participation

Being home to several indigenous communities, majority of native Nilgiri populace is eco-sensitive and they hold the key to the knowledge gap that Sasmitha and others addressed in their above-mentioned paper. The state could perhaps have a committee to study and analyse the indigenous conservation practices often camouflaged as rituals, customs and festivals.

Reverend Phillip K Mulley, renowned scholar and author, explains that the native communities like Badugas, Todas and Kurumbas have sacred grooves around their settlements that have been preserved for centuries. He explains that these forests, later designated as reserved regions, are carbon sinks and people do not venture into these woods except once a year. He has reservations about regeneration considering the increase in population and economic activity and wonders if the state would be willing to allocate more land for afforestation given the rise in land use.

Plastic-free Nilgiris was implemented in 2001 by Supriya Sahu, who was the district collector that year. The residents of the district are entirely responsible for the success of the movement. Eco warriors checking supermarkets and shops were a common sight in the early years of its implementation. From nudging the district administration to act on waste management to installing waste collection bins on the interior roads, various residents’ forums of the major towns like Ooty, Coonoor and Kotagiri have been actively involved in cleanliness and conservation drives in the district.

It would be beneficial to the ecosystem as well the people inhabiting the district if the administration recognised the many pitfalls that could curb the road to a carbon-neutral district and perhaps have regular open house meetings to discuss the future of sustainability. Unlike urban landscapes, the people living in a mountain ecosystem are intrinsically connected to the land, as they have always been.

Read more articles by the author ………