While India aspires to be a $ 5 trillion economy by 2025, a majority of its people are still poor. Despite more than 7% annual economic growth in the last two decades, 80 crore of the total 130 crore Indians are still dependent on free rations.

The bane of India’s development has been the stranglehold of the giver-receiver relationship between the government agencies and the people. Despite spending lakhs of crores of rupees, India’s human development index is something Indians should be ashamed of.

However, a few NGOs have been able to demonstrate that a participatory approach to development is the only way to achieve India’s sustainable development goals. Replicating them and scaling them is key to India’s future.

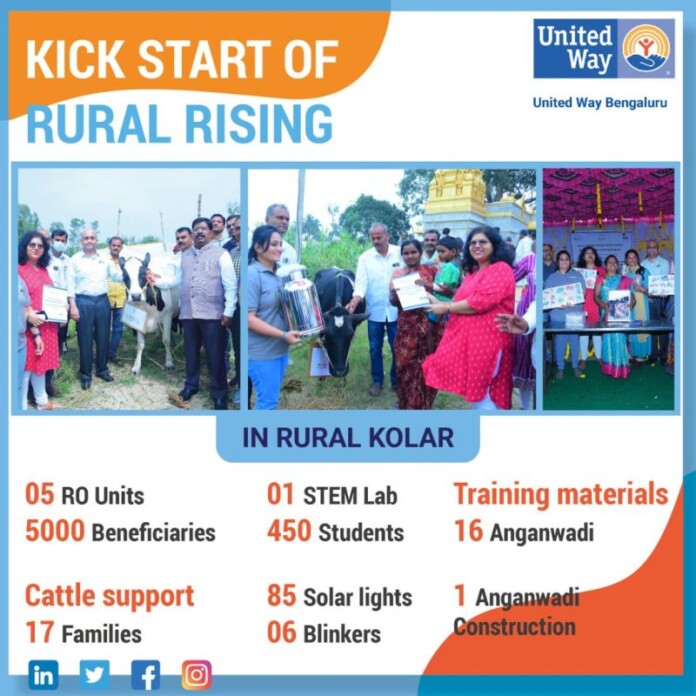

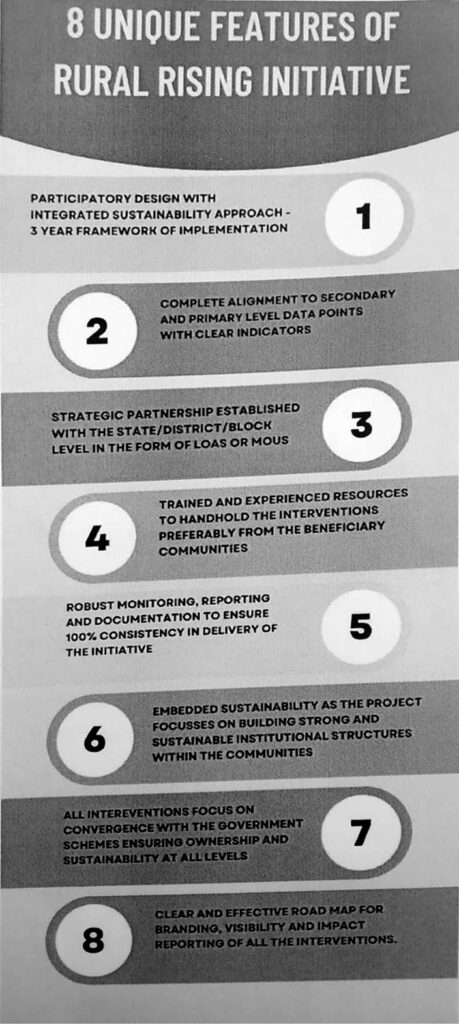

United Way Bengaluru’s Rural Rising project is a case study worth emulating. Established in 2015, in 23 villages of Yelesandra Gram Panchayat, Bangarpet taluk, over 80 kms from Bengaluru, the project has spread to 100 villages around the same region. The NGO has successfully addressed some of the most critical issues faced by rural communities and is all set to expand this model if it is able to raise more funding.

United Way Bengaluru’s significant impact shows that only integrated and interconnected approach is key to building the capacity of rural communities in enhancing the quality of their livelihoods. The four pillars of the project are – education – skill development – health – environmental conservation. All these are interconnected as education is trapped in poverty, poverty is connected to livelihood, livelihood is connected to health and habitat.

True development is possible, as the mission of ‘Rural Rising’ project states, only with assured access to quality education, better health resources, access to improved livelihood resources and clean environment.

Edited Excerpts of a conversation between Rajesh Krishnan, CEO, United Way Bengaluru and Benedict Paramanand, Editor of SustainabilityNext.

Please share a bit of United Way Bengaluru’s history

United Way Bengaluru has a rich heritage, dating back 137 years. It’s one of the largest privately held charities globally, known for its creative fundraising efforts, particularly in the US. What sets United Way Bengaluru apart is its unique franchise model. However, it’s not a model open to just anyone; there’s a rigorous process before any sign-up.

The oldest chapter in India was established in Baroda in 1986, thanks to a visionary individual from Gujarat who had experienced the impact of the United Way Bengaluru in the US and wanted to replicate it here. Today, in 2024, we have seven chapters across India, each with its distinct identity, yet interconnected. Each chapter operates as an independent organization with its board, financial accounts, and registrations.

Despite this independence, we share a commonality through the United Way Bengaluru brand, using the same logo with the city name adapted, like United Way Bengaluru. Globally, there are around 1,100 chapters, with the majority in the US and Canada. Our Bangalore chapter, for instance, is 15 years old and has been actively contributing to various causes.

Notable campaigns United Way Bengaluru has undertaken

The mission of United Way Bengaluru has remained consistent over the years, focusing on improving lives by mobilizing the caring power of communities. One of our notable campaigns is the “Wake the Lake” initiative launched in Bangalore in 2011, which aims to Revive Lake Ecosystem in Bengaluru. It started with urban lakes and has expanded to rural areas. Currently, we are involved in water conservation, afforestation, and soil conservation projects. Our latest major project is the mangrove restoration initiative near Chennai, aiming to rebuild about 100 acres of mangroves in Pulicat Lake, India’s second-largest brackish water lake.

Besides the environment, early childhood education is another significant focus area for us. We operate in about 1,000 centres across seven states, addressing the needs and challenges of the 0-6 age group, which is often overlooked in the broader education sector. We are one of the few organisations working extensively in this space.

What challenges have you faced in your journey, particularly in rural India?

One of the biggest challenges is the distribution of CSR funds. Despite a significant annual CSR budget in India, less than 2% goes to rural areas. Most funds are concentrated in major metros. There’s a need for greater corporate involvement in rural development. Additionally, many NGOs, including us, need to build capacity to absorb and effectively utilize larger funds.

COVID-19 and CSR

The pandemic has been a turning point, pushing many corporations to take CSR more seriously. While the overall CSR funding has remained stable, there’s been a shift towards meaningful engagement with rural communities. We’ve seen about 40-50% of our partners earmarking a significant portion of their CSR funds for rural projects, which is a positive trend.

What’s next for United Way Bengaluru?

Moving forward, we aim to become subject matter experts in specific areas like the environment and early childhood education. We’re also focusing on enhancing rural India’s development through targeted CSR initiatives. Our goal is to bridge the gap between corporate resources and community needs effectively.

CSR Compliance Issues

The government has indeed played a crucial role, especially the Finance Ministry, which could have just mandated a simple 2% CSR spend. However, they refined the process to ensure that the funds are used effectively for the intended causes. This includes holding CEOs and CFOs personally accountable, which has instilled a sense of responsibility and seriousness towards CSR.

Moreover, CSR is now a significant part of board discussions in many companies, getting more attention than ever before. This shift ensures that the leadership is directly involved in CSR decisions, making them more impactful.

Today, CSR is a buzzword in government corridors. Many district commissioners and government officials actively seek CSR funding for their projects. While it’s great to have this visibility, it’s essential to ensure that the projects are genuinely beneficial and not just compliance exercises.

We focus on convergence, where the government, NGOs, and the community work together. For instance, in our livelihood initiative, where we provide cattle to communities, the government supports with funds for building cattle sheds. This collaborative approach ensures sustainable and impactful outcomes.

Convergence Examples

One of our successful initiatives is the installation of solar streetlights in rural areas. This project has brought significant cost savings in electricity bills for the local panchayats and improved security and productivity for the community. For example, a street vendor in Chikkaballapur can now work until 9:30 PM, increasing her earnings and safety.

Such projects not only address immediate needs but also enhance the overall quality of life in these communities. By treating CSR as a social investment rather than just an expenditure, we ensure that the funds have a lasting impact.

Measuring Success

Every project has clearly defined outputs and outcomes. For example, our solar street light initiative includes metrics like cost savings, increased productivity, and improved safety. We focus on realistic and tangible benefits, ensuring that the projects are sustainable even after our involvement ends.

Moreover, we emphasize community ownership. For instance, none of the 700+ solar streetlights we’ve installed have been stolen or damaged because the community values and protects them. This community involvement is crucial for the long-term success of any initiative.

I would urge corporates to view CSR not just as a compliance requirement but as a genuine opportunity to make a difference. By investing in meaningful projects and working closely with communities and government officials, we can create a significant positive impact. CSR should be seen as a social investment that brings tangible returns, not just for the community but for the corporates as well, through enhanced reputation, employee satisfaction, and overall goodwill.

Edited by J Shiruti