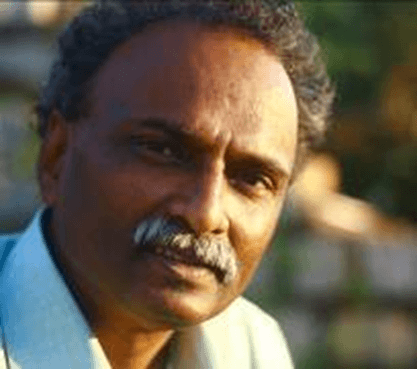

Hariharan Chandrashekar, pioneer of the green homes movement in Bengaluru and a co-founder of Responsible Cities Foundation [RCF), offers viable solutions for city’s energy, water and waste challenges. If citizens take on some responsibility collectively in the apartment complexes, the pressure on the city’s infrastructure and finances will ease and quality of life could go up significantly. Decentralization of production and consumption is the key mantra. Resident Welfare Associations should play a more dynamic role.

In a city of 10 million today, Bengaluru hosts about 2 million homes. About 70% of these are apartments set in dense settlements and high-rises. Where the old lazy town of the 1970s had 20 bungalows to a road of leafy trees, we have today about 300-800 homes packed. The sanitation and fresh water lines were laid largely in the late 1920 to support the city’s water and waste water needs then. As the city grew from a staid 2 million people and 200 sq km in 1980 to its bustle and scream of 10 million people and 800 sq km, clearly the city has to brace up to the challenge of the metro growing to twice its current size by 2030.

City planners cannot do any more than they are seeking to. This is a challenge that goes way beyond what merely good governance – even if we had it – can do. The era of centralized supply of power and water from agencies of the government is now dead. This has to pave way for systems that are decentralized, with independence from the grid that home-owners plan and secure. What can homeowners do to manage the massive shortage of water supply, the mountains of waste that pile up, and about 1.5 billion litres per day of waste water that our homes and hotels and offices disgorge into the canals and lakes?

The city needs today about 2.2 billion units of power every day, about 1.5 billion litres of fresh water [the Cauvery is a finite source and cannot feed any more than what it does now at under 750 million litres a day] with the solid waste spewed by the city every morning put at about 4500 tonnes.

How to Produce Power Yourself

As I said, ‘decentralize’ is the key. Take power, for example. For every unit of electrical power we consume, there is 10 units that have to be produced at a thermal [coal based] or nuclear [uranium based] or hydel [water based] power station. These are at large distances. The transmission and distribution losses, the conversion losses right from basic fuel for the power plants right down to the AC-DC and DC-AC losses account for as much as 90%, though there are experts who argue that it is ‘no more than’ 50-60. Thefts are another challenge if you have to keep economic equations protected.

If you and I chose to produce a mere 2 KW of solar power, and if you are living in an apartment, you installed a biogas digester to convert waste to energy, you will then have met nearly 50% of your power needs within your apartment. This will drop demand dramatically. And ‘upstream’ the demand pipeline you will see a very sharp fall in the need for generation of more central grid power.

For at least the last ten years, solutions have been staring at our face but governments resisted for they were apprehensive of the technology and the lure of massive public expenditure that power sector offered was hard to resist. But with the crashing of solar installation costs by 75% from 2010 to now, and the rapid rise of a new generation of solutions and systems that offer such decentralized power right at your door, there is simply no excuse for home-owners and bulk-users of power in hotels, hospitals or offices, to be continuing to depend on the grid.

If all homes installed even 1 KW of such local solar power, the city’s demand for power will fall to one half its current levels. Government agencies and utilities can manage that much better. The cost of setting up 1 KW is about Rs. 1.2 lakh, but when it does as a community or apartment this can be as little as Rs. 70,000 for the need for inverters and batteries are eliminated. If there is excess power that the community generates, the grid is willing to buy it back at a cost that makes it viable. There were initially some hiccups in such ‘grid exchange’ but those have been smoothened.

If there is wet waste of 500 kg to an apartment complex or a layout, you can produce as many as 20 cylinders of 20 kg equivalent of gas for your kitchens and heating. These can be used for common areas. If the waste-to-energy option is not making sense for an apartment, they could look out waste-to-compost. Essentially they would have stopped dumping waste on the streets for the city corporation to transport and dump them in those miserable dump yards across the city periphery. They are hazardous, and seriously hurt the neighbourhood that has to host such massive mountains of waste. This is apart from the saving in costs of transport – the BBMP pays up to Rs. 800-1000 crore [no firm figures are of course available] every year with nearly 500-700 vehicles that haul such waste and add to the traffic every day.

Recycle Waste Water

So is the case with water. If we recycled waste water and used them for gardens and car wash, there will be a 60 % drop in demand for fresh water. If the city’s daily demand falls from 1.4 billion to about 800 million litres, you can see how we will have eased, as consumers, the impossible challenge that the government continues to carry.

What we do not realise is that you pay as a domestic buyer of water about Rs 8 to every thousand litres [or Kilo Litre]. The Water Supply Board incurs a staggering Rs 95-100 per KL for supplying that water to you. It has become hugely unviable. This has been so for many years and no one notices. Politicians dare not touch this ‘holy cow’ and so suffer the deficits by meeting these massive deficits month after month.

Air quality in this city as in others in India is a challenge. The air in Bangalore is thin because of the altitude – we are one kilometre above sea level. Its ability therefore to absorb particulate matter is far lower than in coastal cities where the air is denser and more humid. Again, governments can do little. And the IT sector’s unbridled growth in the city has meant about 400 million tons of central air-conditioning that has recklessly been installed by these companies without heed to the grave consequences that these ACs bring to air quality.

In essence, the city’s RWAs – there are over 2000 of them by some estimates – should act. They should listen, learn, invest a little bit, make back that money within 2-4 years as ‘payback’ and bring for themselves not just assurance on energy and water supply, but increased quality of health with what they can do to manage waste and install little inexpensive things that enhance quality of air in their buildings.