In a first, Meghaa Gupta, Editor (Youth) at Sustainabilitynext.in reflects on green books published for young people in India and despite the challenges, finds much to be pleased about.

So little (relatively) is written about young people’s literature published in India, let alone green literature, that I would like to begin this column with the hope that the tide turns, sooner than later. Because we live in the perilous world of human-induced climate change and we need stories that allow us to hope and help us imagine a better future. Yet, any talk of this future is futile if we don’t think of young people who will inherit and take forward the planetary legacy we leave behind. So, any talk of stories is futile, if it doesn’t involve stories we’re writing for and sharing with the young people of today. The good news is – there are plenty of stories. And if surveys in recent years are to be believed, this number will only increase.

In 2019, data from Nielsen Book Research revealed that the number of new children’s books looking at the climate crisis, global heating and the natural world had more than doubled and sales too had gone up. Publishers around the world called this ‘the Greta Thunberg effect’, after the Swedish youth activist who arrived on the world stage in 2018 and sparked off a global, youth-led movement against climate change, leading to a groundswell of young people’s literature on the environment. Although there appears to be very little formal mapping of this trend in India, in his presentation at the Neev Literature Festival in September this year, literary agent Kanishka Gupta corroborated that there has indeed been a huge surge in the number of Indian children’s books (fiction, non-fiction and picture books) on the subject. He cited books by Bijal Vachharajani, Rohan Chakravarty and this writer, as critical and commercial successes.

Indeed, the last few years have seen the release of some much talked about books on the environment. One of the most prominent voices to have emerged is Bijal Vachharajani, whose novel on climate change, A Cloud Called Bhura (Talking Cub, 2019) became hugely popular – only to be topped by her second novel on the subject, Savi and the Memory Keeper (Hachette, 2021). This year, saw the release of Vachharajani’s Help, My Aai Wants to Eat Me! (Puffin), a hilarious early chapter book about a boy who is frightened that his mother, like some mothers in the wild, has cannibalistic tendencies.

From doyens like Ruskin Bond, Ranjit Lal, Stephen Alter and Zai Whitaker, to relatively new voices like Bijal, Nandita da Cunha, Yuvan Aves and Arefa Tehsin, it’s interesting to note that despite its relatively low-profile, there are many writers in India consistently producing environmental literature for young people. Apart from Bijal’s latest book, this year also saw the publication of da Cunha’s My Trip to La La Land (Harper Collins) set in a mountain school in Ladakh, Aves’ Shorewalk (Tulika) about creatures inhabiting Chennai’s beaches and Tehsin’s Iora and the Quest of Five where human and forest worlds collide, leading to a wild adventure.

Biographies

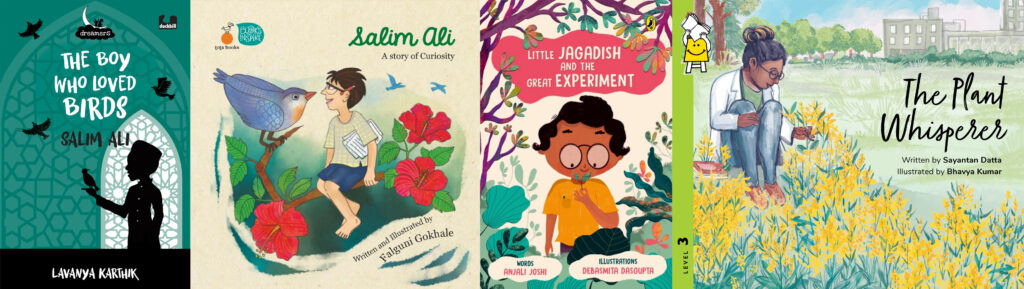

Biographies have always been popular and 2022 was no exception. Ornithologist Salim Ali a.k.a the Birdman of India, was featured at least in two books: Lavanya Karthik’s The Boy Who Loved Birds (Dreamer Series, Duckbill) and Falguni Gokhale’s eponymous Salim Ali: A Story of Curiosity (Tota Books). Scientist Jagdish Bose too is a popular figure in children’s literature and this year saw yet another book on him: Anjali Joshi and Debasmita Dasgupta’s Little Jagadish and The Great Experiment (Puffin).

There is a legion of personalities who have made vital contributions to the environmental field in India. Yet, very often children’s books veer towards the usual names. So, it was good to see titles like Karthik’s The Girl Who Climbed Mountains (Duckbill) on mountaineer Bachendri Pal, and Sayantan Datta and Bhavya Kumar’s The Plant Whisperer (Pratham) on ecologist Jaishree Subrahmaniam. One hopes to see more diverse names being brought up in children’s biographies. I’m particularly keen to see more books on the contributions of environmentally-conscious writers and artists. Barring Bijal Vachharajani and Radha Rangarajan’s 10 Indian Champions Who are Fighting to Save the Planet (Duckbill, 2020) and books about the artist Mehlli Gobhai, one cannot seem to find other titles in recent times that have covered such personalities.

Wildlife

A similar problem seems to plague children’s books on wildlife, where we see an overabundance of books on elephants and big cats, particularly tigers. This year, Talking Cub published Grandfather’s Tiger Tales. A few months later, it released The Tiger of the River that cleverly rides on the tiger’s popularity to speak about the mahseer, a critically endangered species of fish. Towards the end of the year, the publishing house brought out wildlife conservationist Prerna Singh Bindra’s When I Met Mama Bear: A Forest Guard’s Story. Another interesting book was Varsha Seshan’s How Big is a Whale Shark? (Pratham) that used this fascinating extant fish to weave a simple lesson on sizes. The only quip I had was that it didn’t include any additional note on these creatures, that don’t usually find their way into children’s picture books in India (which in itself is a quandary).

When we speak of wildlife, we tend to overlook the inanimate plant kingdom. Fiction often reminds us of trees through tales built around people wanting to chop them down. Tanya Majumdar’s The Monster Who Could Not Climb a Tree (Kalpavriksh) was a charming addition to this corpus with delightful illustrations by Rajiv Eipe. Meanwhile, Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli’s So Many Leaves (Pratham) offered yet another window to go out and observe the plant life around us.

The food chain is vital to the sustenance of life. It also offers a fertile premise for children’s books. How the Myna Ate the Sun (Pratham) took an unusual and vividly illustrated approach to the subject by highlighting the central role of the Sun.

Landscapes

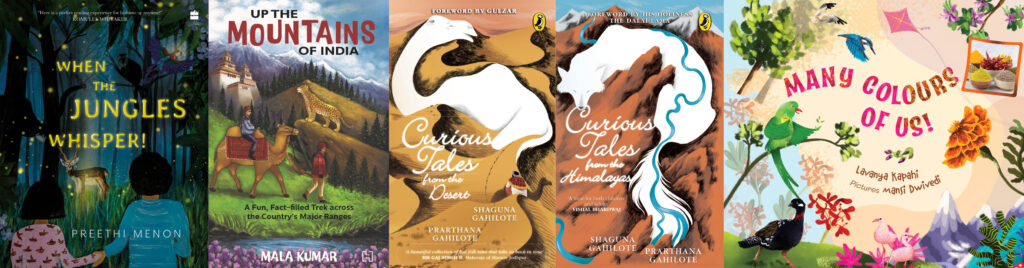

Landscapes form yet another theme in environmental literature. Here too, one can find many books on forests. Preethi Menon’s collection of short stories, When the Jungles Whisper (Harper Collins) traipsed through several jungles and forest reserves in India. There were also at least two books on mountains: Mala Kumar’s comprehensive non-fiction Up the Mountains of India (Hachette), and Shaguna and Prarthana Gahilote’s Curious Tales from the Himalayas (Puffin), a collection of folk stories. The latter also brought out Curious Tales from the Desert. Pink flamingos in Kutch, purple Naga chillies, black Bhadra panthers… Lavanya Kapahi’s Many Colours of Us! (Tulika) combined colours and wildlife to paint a vivid portrait of places across the country.

However, not as many books have been written about landscapes like marshland and one hopes to see more young people’s literature set in these underrepresented geographies.

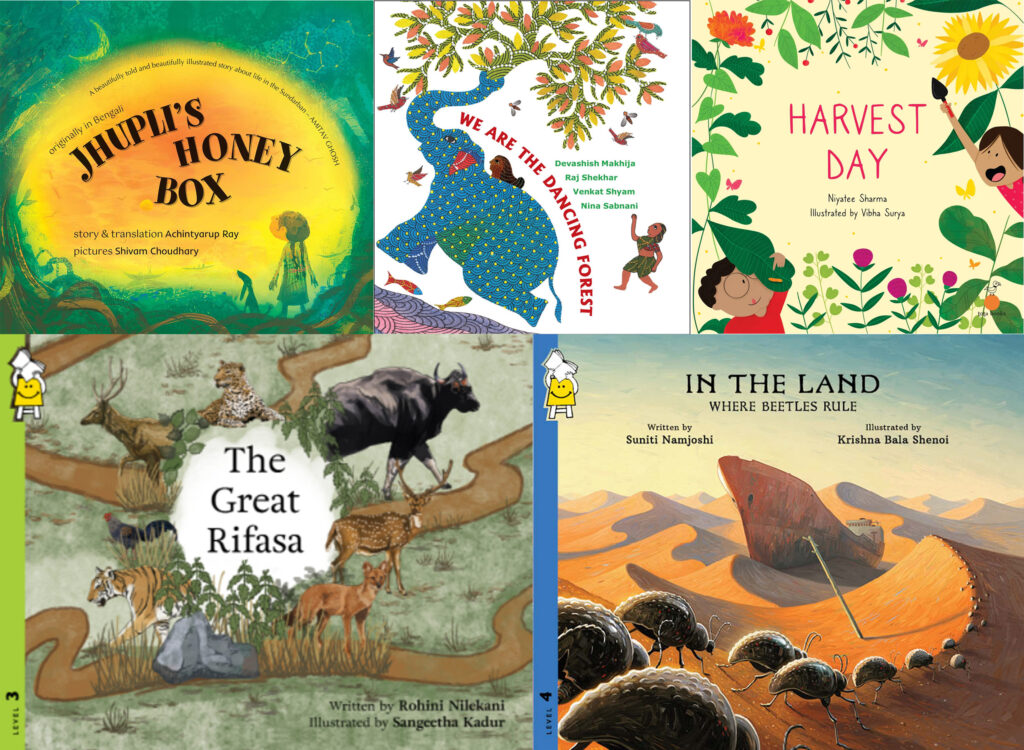

Tales of our inter-connectedness

At the end of the day, most narratives on nature attempt to break through the historically cultivated nature-culture binary to offer stories that remind us of our interconnectedness within the web of life. This has come into sharper focus because of COVID 19, a virus that jumped across species because of human violation of the natural world. Philanthropist Rohini Nilekani took an intriguing view of this divide in The Great Rifasa (Pratham). Set against the backdrop of the pandemic, it had animals in a national park missing human tourists. Jhupli’s Honey Box (Tulika) narrated a poignant tale about the vulnerability of life in the mangrove forests of the Sundarbans. Suniti Namjoshi and Krishna Bala Shenoi’s In the Land Where Beetles Rule (Pratham) gave readers a stunning peak into a world without humans. Raj Shekhar and Devashish Makhija’s We are the Dancing Forest (Tulika) offered a magnificently illustrated adivasi song set in the beating heart of a forest where life dances to the rhythm of the natural world.

Books on nature-dependent livelihoods, that speak of human interaction with the natural world through activities like fishing or the growing of crops, are crucial to any discourse on the nature-culture intersection. Yet books that cover such themes often fall outside the spotlight. Recent books that I recollect are No Nonsense Nandhini (Karadi) about a woman farmer and Bombay Ducks, Bombay Docks (Pratham) about the Koli fisherfolk of Mumbai. Niyatee Sharma’s Harvest Day (Tota Books) was one of the few books on this theme, published this year.

Surprisingly, I didn’t hear of any major titles featuring extreme weather and climate change for children, this year. Quite sure there may have been some edifying non-fiction, but it didn’t reach me (not that I’m complaining). At least nothing that seemed to break a mould… except perhaps Manu Bhattathiri’s delightfully whimsical story from the anthology of the same name, The Greatest Enemy of Rain (Aleph). And how I wish, we could have him write an entire collection of such stories on extreme weather and the people stuck in it, the suffering, the abysmal infrastructure, political ineptitude…

Playing with Form

There is much scope in playing with form, when it comes to books on the environment. A wealth of nature-based art yet to be exploited. It’s been fascinating to see how artists and illustrators have incorporated everyday waste into children’s books like Ammu’s Bottle Boat (Tulika) and Art is Everywhere: Here, There and in Trash. Tara books, Chennai, is known for consistently stretching the boundaries of the book form. This year, they published French artist Anaïs Beaulieu’s A Stitch Out of Time featuring images of her exquisite embroidery on throwaway plastic bags.

A Parting Note

Under the aforementioned themes writers and illustrators attempted to enthral young readers with adventure, fantasy, drama, humour… all the makings of good, old storytelling, often accompanied by vibrant visuals. They used literature to touch upon history, geography, some science and a lot of heart. Even though this column is limited to English literature by a handful of publishing houses that bring out books for young readers, some of these books, particularly those by Tulika and Pratham, are available in other Indian languages and I’m almost certain that there are many other titles that I still need to explore. So, it’s with a happy smile that close my first column – assured of a nice reading list, many more book reviews, features, interviews and latest releases on Sustainability Next’s youth pages that are now over a year old! I’m also keen to see the final master list of young people’s literature for next year’s Honour Books at the Green Literature Festival. Till then, wishing everyone (who has bothered to read till the end!) a peaceful year-end and a spectacularly green new year.

Meghaa Gupta curates the young people’s programme at the Green Literature Festival. She is the author of a series of history books on Independent India, published by Puffin – the children’s imprint of Penguin. These include Unearthed: An Environmental History of Independent India (2020) and After Midnight: A History of Independent India (2022).