Citizens wonder why their cities are unable to manage the waste problem and take the easy route of blaming corporators. Here are a few lesser-known reasons that are hindering the progress of waste management

The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan has brought waste management into everyday consciousness, which is good for all concerned including citizens, waste-pickers/sanitation workers and waste management service providers. However, along the way, a myth has been created right from the Prime Minister’s Office to technology providers to a well-known national brand that there is “Wealth in Waste” and therefore there is no need for citizens to pay for responsible waste management. This article is an attempt to unravel the reality of responsible waste management economics.

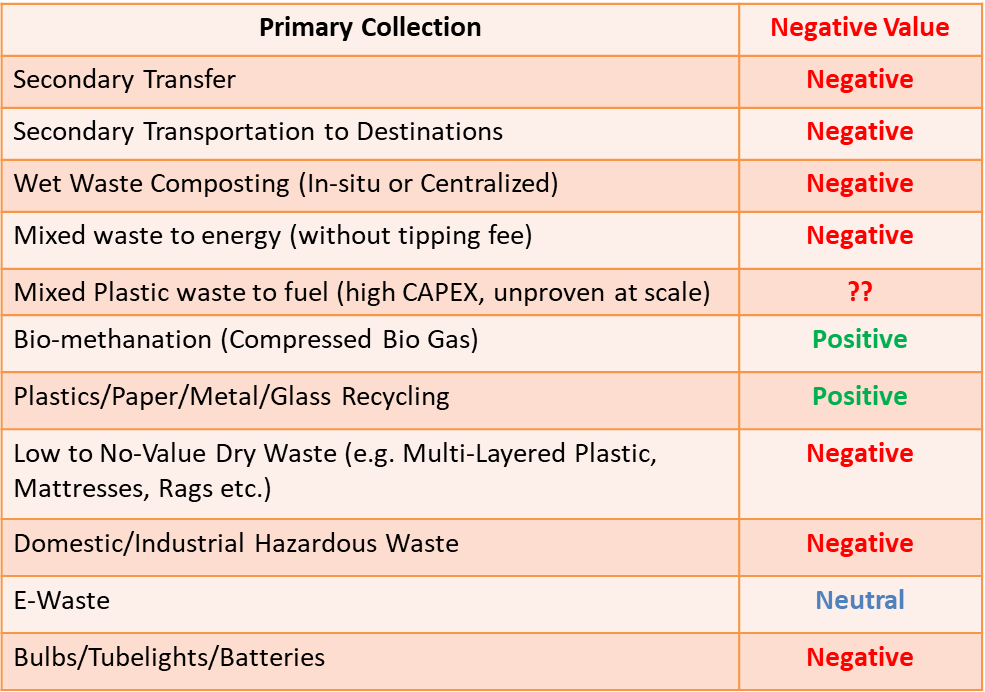

The first thing to understand is that the end-to-end chain from pickup of waste from the source of generation to the end of the pipe of responsibly processing or disposing the waste is a negative value process. Even with today’s cutting-edge technologies, the cost, time and labour required to responsibly collect, transport and process waste is higher than the revenue that can be generated from transformation of waste into something of value – be it energy, compost, biogas, fuel, recycled to original material, repurposed usage, refurbished products or disposal in scientific landfills.

There is also the issue that since the points in the value chain that generate positive margins are not necessarily integrated with the first mile of collection and transport, the positive value is not shared across the value chain.

The table below gives the different elements of the value chain and its value creation – negative or positive.

Many of the problems that we face today in cities being able to manage waste effectively is this lack of understanding of the economics of waste management. For example, many urban local bodies who take up the responsibility themselves or through tendered contractors’ primary collection, secondary transfer and transportation to destinations grossly underestimate the costs involved.

A study of tenders floated by ULBs tenders for door-to-door collection and transport (C&T), the estimated tender value was significantly below conservative costs for the required SLAs (service level agreements) and this without including corporate overheads and profit margin of the service provider. Since L1 (lowest price) is the basis of decision to award a contractor and estimated value is the guiding price, those who win the tender can make the project viable only if they cut corners or resort to corrupt practices leading to uncollected waste, illegal dumping etc. which is what we see across the country.

Who Should Pay?

If the above is accepted, then the obvious question is who should pay so that waste can be managed with least to no negative impact on the environment. There are only three stakeholders who can absorb the negative value

- The waste generator (consumer/communities)

- The Producer of the products whose consumption leads to waste

- The Government as waste management falls under its purview

The Waste Generator

The waste generator should bear part of the cost through what is universally accepted as the “polluter pays” principle and should ideally cover the C&T till destination including any tipping fee charged by the destination – processor or landfill operator. The Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 allows for the charging of a user fee. To make it equitable, a “pay as much as you generate” pricing model can be implemented like a company has done in Bangalore for bulk waste generators. In addition to paying the user fee, the generator has one critical responsibility – to segregate waste at source into three streams – bio-degradable wet, non-biodegradable dry, and domestic hazardous waste (aka rejects like sanitary/diaper waste, medical sharps). Without this, the costs of segregating down the line goes higher and the percentage of material recovered for recycling becomes lower.

The Producer

The producer should take responsibility for the collection and processing of the waste that the consumption of their products generates. This has been encapsulated in the “Extended Producer Responsibility” (EPR) concept pioneered in Europe and now part of India’s Plastic Waste Management Rules 2016 (amended 2018) and eWaste Management Rules 2016. The producers can work with waste management companies to ensure recovery of the waste generated be it the packaging or managing the end-of-life of their products and pay for the costs of the same. This however is only a halfway measure. If the producer wants to make a real impact on the circular economy, they should design their product to produce less waste on consumption if is a consumer non-durable and if it is a consumer durable then repairability and recyclability must be designed in. They must move from minimizing “cost of production” where waste management becomes an externality to be borne by society or government to “cost of consumption” where it is accounted for before the sale is made to the consumer.

The Government

The Government has traditionally used tax money either raised through specific garbage/SWM cess or through their revenue from property tax to cover the costs of waste management. As mentioned earlier, since ULBs are not very good at estimating the true costs leading to shoddy work, it is recommend that they implement the policies already in place and monitor the same closely so that the costs can be absorbed through ‘user fee’ and ‘EPR’.

The role of the government should be to implement progressive policies and provide a critical component – land and infrastructure for transfer stations, Dry Waste Segregation Centres (DWCC) (aka Material Recovery Facility (MRF)) and waste to value processing facilities like plastic recycling plants, hazardous waste incineration, low-value plastic to fuel facilities etc.

No discussion on who pays for it is complete without talking about the much-touted Waste-to-Energy (WtE) through burning of the waste to produce electricity. No WtE plants are viable without government subsidy or tipping fees even in the developed countries. Secondly, the waste composition in India has 50% to 65% of wet waste which brings down the calorific value of the waste due to high moisture content. Because of this no plant in India so far has successfully operated in the long run. Finally, the CAPEX per ton is exorbitant making it a non-starter as a solution across such a vast country such as India. But WtE continues to fascinate the powers that be as it is seen as a simple, almost elegant, solution and the high project outlays are another attraction. It is this author’s recommendation that if the above is implemented, our cities will be clean as well as help reverse climate change impacts due to irresponsible waste disposal. At the end of the day, sustainability must meet financial viability and understanding the economics of waste management is the first step.

a

Support Green Journalism

Dear Readers,

Since March 2013, SustainabilityNext (SN) has been educating and exciting thousands of entrepreneurs, executives and graduate students about the power of Sustainability in influencing our future. It’s purpose is to inspire and provoke Indians to move swiftly from awareness to belief to ACTION.

As of December 2021, SN is India’s most read digital magazine on the business of sustainability. It has been covering Green Business, Green Products, Social Entrepreneurship, Green Literature, Green Technology, among others. A youth section was added in 2021.

SN launched India’s first Green Literature Festival (www.greenlitfest.com) in June 2021 to offer a robust platform for readers and writers to hold meaningful conversations.

For SN to grow and stay relevant it needs to transition from a grant and self-funded model to a community-funded and/or institution/corporate-funded model.

Looking forward to your timely and generous support.

Why Support SN – https://sustainabilitynext.in/support/

Subscriber

Supporter

Benefactor

Sponsor

All supporters get two-year subscription to SN. You can Gift Subscription to your colleagues/friends/family.

For sponsorships and advertising please contact

Benedict Paramanand

Publisher & Editor

benedict99@gmail.com

a