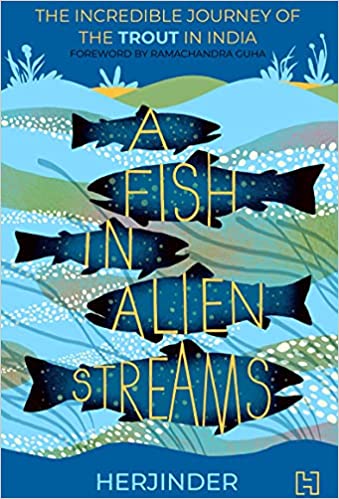

The history of colonisation in India usually talks of the military, economic and political occupation of the country by imperialists. Rarely, does it talk of how homesick colonialists altered their surroundings to make them more akin to their homeland. How they dotted the landscape with their manicured gardens, clock towers and other colonial structures – and as this book, A Fish in Alien Streams narrates – populated its rivers with their favourite trout!

I’m neither a fish-eater nor have I ever attempted fishing. Yet I enjoyed reading this delightful slice of our colonial past festooned with several lively excerpts drawn from an impressive collection of personal letters, books, magazines, journals and the like. For instance, the first chapter of the book begins with a letter from 17 June 1856 that Henry Stedman Polehampton, chaplain of Lucknow, wrote to his brother in England:

My Dear Edward,

Pray do send me a diary. Every scrap from England is interesting, and your letters are feasted on as they arrive. I thank you for your fresh assurances of affection to me…

I had in my mind’s eye at the moment our paddling up that brook at Pontesbury together last summer. What a pleasant day that was, and what a nice lot of trout we killed!

From here on, the narrative goes on to unravel how during the 19th and 20th centuries, many Europeans in India – an assortment of company employees, army officials, Christian missionaries etc – were pining for the salmon and the trout – superior game-fish of their native land. Many tried searching for similar species in Indian streams. In his book, The Rod in India, published in 1873, Henry Sullivan Thomas of the Madras Civil Service wrote of the legendry Indian fish, the mahseer:

…I say a Mahseer shows more sport than a salmon… each individual Mahseer makes a better fight than a salmon of the same size… my prejudices were all in favour of the salmon, a sort of lion of the waters, whom I have grown up looking on with respect from childhood, and as being a fellow-countryman. But the Mahseer compelled me to… honour him in spite of my prejudgment to the contrary.

I was amazed to find many such impassioned narratives built around fish, in this book. It was even more surprising to learn about the lengths to which a clutch of British anglers (people who fish with a fishing rod, as a hobby) went, to import trout into Indian waters – simply because it made for a better fishing experience!

As historian Ramachandra Guha points out in his foreword, “the effort – in time, money, intellectual focus and organizational effort – was colossal, almost comparable to fighting a war even.” Yet the passion was so intense that despite the failures, they persisted and eventually succeeded in breeding the trout in the rivers of Kashmir, and from there on, in many other parts of the country and even in Ceylon.

The narrative takes us through all these geographies and the unique challenges they posed to the fish. But the trout proved to be resilient and eventually began to thrive in many streams across the subcontinent.

All this took place at a time when even the term ‘invasive species’ had not been coined. So, hardly anyone was thinking of the ecological and environmental concerns in adding a new species to an ages-old ecosystem. Most were gloating over introducing a ‘superior fish’ into Indian waters. Yet, as the author concludes from his research, this exotic species were far from being in harmony with the local ecoclimatic conditions. So, once their patrons left the country, these fish too began to decline.

Today, they are largely restricted to streams in and around Kullu, where the author, Herjinder, encountered them in 2009. A journalist by vocation, he had been sent on an assignment to a trout farm to cover 100 years of the introduction of trout in Himachal Pradesh. However, as he found, the newspaper feature could hardly begin to cover this fascinating story of immigrant fish that made Indian waters their home. So, he spent a decade researching it.

Even though the subject may sound specialist, the narrative is light, lucid and peppered with tales from a colourful cast of fishing enthusiasts. My only quip, if at all I need to make one, is that I wished the publishers and author had also included a few visuals to complete this otherwise wholesome portrait from our past. Unlike cricket, the British passion for fishing didn’t quite hold in independent India. So, a visual sense of how the various fish being spoken about looked, a few newspaper clippings, photographs of anglers with their trout catch etc might have aided lay readers a little better. Nevertheless, if you’re a nature lover, do add this enjoyable and enlightening read to your bookshelf. It is a unique contribution to the natural and social history of British colonialism in India.