By Jonathan Porrit

Here is an amazing statistic: oil production last year was down to around 4 million barrels a day – from a high of 76 million barrels a day in 2017. The age of oil is well and truly over – and, happily for all of us, civilization hasn’t collapsed!

I was in my late teens in 2017, but can still recall the most apocalyptic tone in which people used to speculate about the so-called ‘peak oil’ moment – the year in which we took more crude oil out of the ground than in any other. The answer it turned out was 2017, and the amount was 76 million barrels a day. While the world did not grind to a halt after this, few countries were properly prepared for the profound changes that ending their dependence on oil entailed – despite having had decades to get themselves ready.

Oil’s last gasp

The peak oil moment might have come a lot earlier were it not for the last – gasp efforts of the oil companies as they took advantage of very high oil prices to go after the oil that would otherwise have been way beyond their reach, geologically and economically – especially from reservoirs in very deep water or very harsh conditions in places like the Arctic.

There were also very unconventional sources of oil and gas that added another 10 to 15 million barrels a day, such as tar sands – a kind of cloggy, bituminous fuel that had to be heated up before it could be extracted. Billions of dollars were spent on developing Canada’s tar sands between 2005 and 20018, despite endless warnings this was sheer madness: a barrel of oil from tar sands emitted at least 50% more CO2 than a conventional barrel – at a time when we were already trying to reduce CO2 emissions per barrel. Investors in the tar sands got horribly burned in 2018. After the Emergency Report of 2016 from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the USA grudgingly agreed to follow Europe’s example in setting very tough carbon By Jonathan Porrit standards for liquid fuels – which the oil extracted from the tar sands simply couldn’t meet – primarily because of the impact of weather-related disasters on public opinion. The Canadian economy nose-dived, so great was its dependence on oil exports to the USA and it didn’t properly recover for another five years.

There was no going back when a year later a disastrous release of waste water from one of the largest tar sands operations, contaminated with mercury, lead and other toxic elements killed off almost every living creature along the 160 kilometer stretch of the Athabasca River. It’s taken the Athabasca a full 30 years to recover.

The next 30 years after the peak oil moment was a story of managed retreat away from oil. Of the 4 million barrels a day used in 2048, almost all was used in aviation, shipping and the production of high-value chemicals. In 2017, there were 708 oil refineries operating worldwide; today, there are just 11 – two in the USA, two in China, one each in Brazil, the Netherlands, Indonesia and India and three in the Middle East (Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia and Iraq).

We shouldn’t beat ourselves too much here. Oil was cheap and easy to get (until the turn of the century) and it was energy-dense, delivering a lot of energy for not much volume. It was also incredibly versatile, providing not just liquid fuels but also the basic feedstock for the entire chemical industry from plastic to pharmaceuticals’- even though no more than five percent of the oil was used for these purposes. So it was highly addictive – as a former US President, George W Bush once acknowledged.

Today’s algae-based materials are now so cheap and useful that they have displaced almost all of the oil we once used for plastics, pharmaceuticals, paints, lubricants and so on. They still can’t quite provide everything we need – hence the continuing requirement for small amounts of high-quality crude oil. Although for how much longer, I have no idea. As my daily Green Stream bulletins from the New Scientist keeps reminding me the pace of innovation is as intense today as it’s ever been. Give us another 20 years and I suspect we will be down to a few hundred thousand barrels a day from those superefficient oil wells in Iraq. And that will be it.

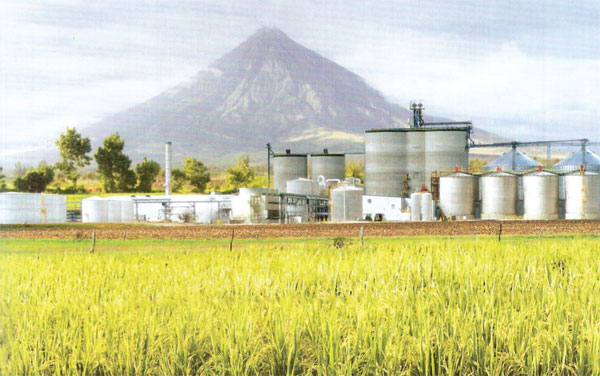

The Philippines: A case study

Here is a case study that my researchers have unearthed. Back in 2015 the Philippines was a very poor country, made all the poorer by unconstrained population growth. So punitive was the cost of importing that the Philippines government took the bold decision in that year to become the world’s first all-renewable country. It already had a lot of hydro and geothermal power to which it then added wind and solar on a vast scale. But the real breakthrough came with the revolution in the use of biomass. As a predominantly agricultural country the Philippines can call on huge amounts of forestry and agricultural wastes from the production of rice, sugar, maize and coconuts. With major support from the Asian Development Bank investment in bio-refineries and biomass power stations (using rice hulls and straw and maize cobs and stalks, coconut husks and the like as furls) took off in the early 2020s.