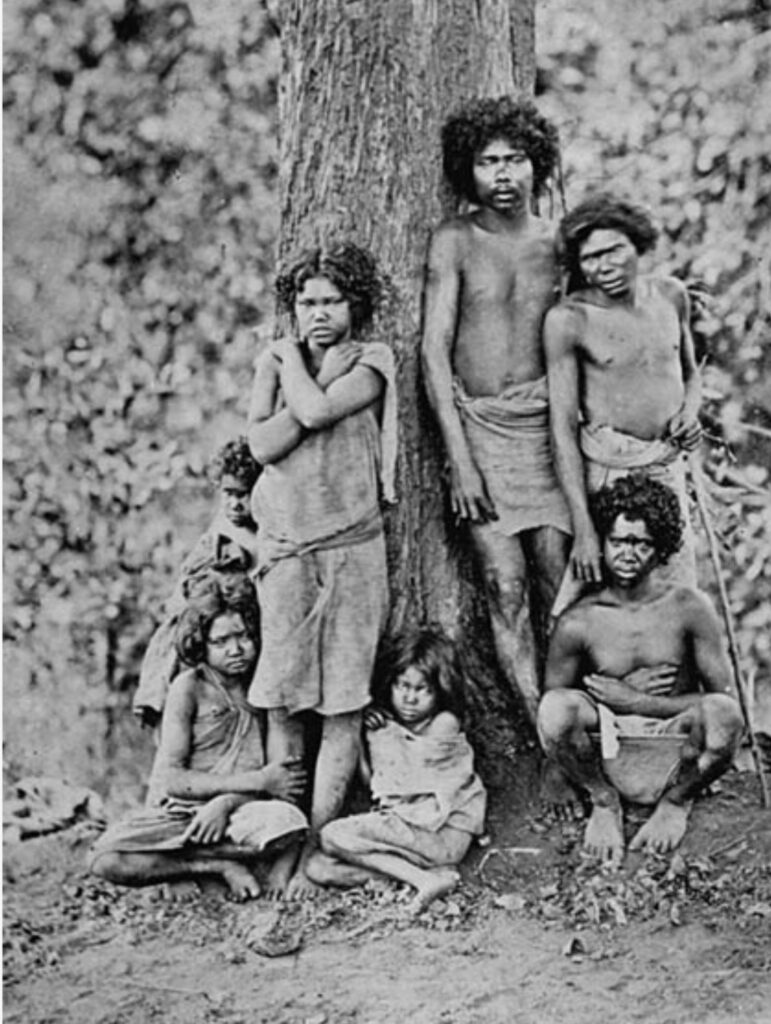

On the 200th Year of Ooty’s formation, SustainabilityNext brings to you a conversation between two indigenous women on the meaning of conservation and preservation in the Nilgiris.

I met Vasamalli, a Toda scholar and activist on a cold October morning, shortly before the advent of monsoon. The moisture-laden northern wind blew with an intense force in her mund, a Toda hamlet in Ooty or Ootacamund surrounded by tall peaks and pristine meadows. Not many people know Ootacamund is derived from Hotteikalmund, the mund here denoting the Toda hamlet that it was.

I confess to Vasamalli that despite being born in a Baduga community and raised in The Nilgiris, I have never entered a Toda mund. She laughs and tells me that our connection dates back millennia, probably more.

Our conversation touched upon history, indigenous belief systems, conservation, folklore and the mountains our ancestors revered.

Excerpts

Can you tell me more about your journey before we begin

After completing my SSLC here in Ooty, I went to college in Coimbatore with the aid of Dr Narashiman, a general physician and philanthropist who was practising in The Nilgiris. His family looked after me and attended to my many needs during that period. After that, I returned to Ooty, took up employment in a public sector enterprise, met a kind man and married him.

My husband was a brave man who had dreamt of reforms for our community. Together we realised that we need to bring in change both internally within our community and externally to aid our advancement in the world. It has been a few years since I lost him, but I still follow his path and represent our community where I can.

Let us go back in time. There are many opinions about the origins of the Baduga community and on our time here in The Nilgiris. This is a drawback of having no documentation. How long have The Todas inhabited this mountain district?

The practices of both our communities certainly predate the Anthropocene period. The rituals that are prevalent until today, our way of life that prioritises the environment and the messages hidden in our prayers and stories are all markers of an ancient society. There is no definite number, but an old storyteller I was acquainted with told me that the Toda community may have lived here for over 35,000 years.

That is fascinating. Strangely, we know the sites of dolmen and other megalithic structures. The people in our communities even consider them divine. That brings to my mind the notion of sacred to an indigenous person. For us, it is the peaks, the valleys, the trees and the rocks.

Yes. Among the Todas, we have a name for every peak, hill and valley. These hills have a gender too and we name our infants after them. This implies the reverence that is accorded to them. We have a folklore associated with many peaks and lakes. We recollect some of them during rituals and prayers. Every aspect of living is intimately connected to the land we live in.

Interestingly, you mentioned folklore. I am fascinated by these stories that are connected to landscapes. There is so much information in them and for indigenous communities worldwide relying on oral traditions, these tales carry nuggets of age-old wisdom. Can you tell me some that you know?

Sure. To the west of Ooty, on the road connecting Gudalur, there is a viewpoint. The chain of mountains that you see from there is sacred to us. You can spot a small conical- shaped hill named Ottarsh (by our ancestors) amidst the tall peaks. We believe that our holy group of buffaloes Thee Eer originated from this mountain’s sweat. The entire chain of mountains in that locality is considered sacred. (This is picked from the several folk tales that Vasamalli was kind enough to share).

In your journey, have you encountered any kind of threat to these ecosystems. I am not talking about natural events but interference from people. Have you handled any?

There have been many. We can start from the origins of this town to what it is today. As you know before Ootacamund was developed as a town, it was just grasslands with a few munds. It is said that John Sullivan, the then collector who developed Ooty negotiated with our people. Every time, there is development in living conditions, the land is ravaged and along with it the people closely connected to it are affected.

In the recent past, there was a drive by the local administration to plant eucalyptus trees on the peaks adjoining Ottarsh. Some peaks already have this water-intensive crop that was planted decades ago. I wanted to save the few peaks that had grasslands. I gave a petition to the collector and the plan was cancelled.

With climate change there is a growing fear of apocalypse. There is more emphasis on conservation now. For communities like ours it has been a way of life. We have preserved several groves and peaks. Is there anything we can contribute to this global fight against climate change?

For us, preservation is conservation. Around our munds and hattis (Baduga settlements), we have what you call sacred forests and peaks and sometimes, the whole hill is worshipped. We have conserved by not extending our villages there and preventing economic activities. What else can we contribute other than the intrinsic knowledge of our ecosystems handed by our ancestors and our practice of minimalistic living?

Let us talk about the present. We know that any change or advancement in a society has perks and drawbacks. This generation of Badugas has moved to cities across the world in different professions. The people living here are dependent on tea plantations and agriculture and some are employed. Plantations are not sustainable anymore. We lost touch with the part of us that were pastoralists. I know the scenario is similar to an extent in your community. The generation after yours is employed, some in the vicinity of their residence. People depend on livestock partially and women generate income through their artistic legacies.

Yes. Our Pukhoor (Toda embroidery) has a GI tag. This embroidery, as you said, is a legacy given to us. We use a specific darning needle and the end-product has an impeccable finish. Traditionally our ancestors wove what they observed around them. So, the motifs of the design vary from the moon to buffalo horns or reptiles. Today we work with foundations that display our products in their retail outlets in the district and even private retail outlets and individuals who travel to source them in bulk. We make products like wallets, purses, mobile pouches, totes, jackets and shawls. This vocation garners buyers throughout the year.

Our buffalo numbers have dwindled over the years. It is not sustainable anymore. Our people residing here in the district are employed locally. There has not been a large-scale transition in our living conditions as your community has seen, but we are still connected to our roots.

Can we talk about our future that is connected to the future of the mountains.

It worries me that our youngsters do not attempt to learn in-depth about our culture and the richness of our traditions. However, I’m glad that they participate in the community events. What can we do apart from hope that our people and our traditions live so that the mountains are safeguarded.

Monisha Raman is a freelance writer and editor.